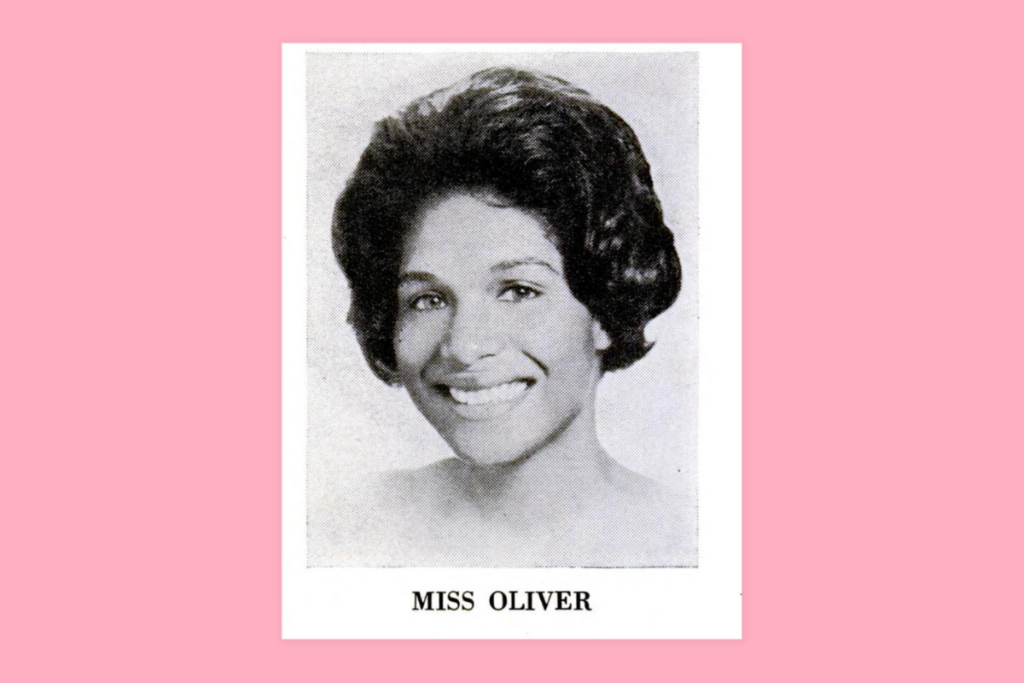

On Episode Nine of Ursa Short Fiction, Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton kick off a two-part book club discussion on the life and work of Diane Oliver, who published six short stories before her life was tragically cut short in May 1966 at the age of 22.

Oliver was just a month away from graduating from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop when she was killed in a motorcycle accident in Iowa City, Iowa.

Philyaw and Walton first discovered Oliver’s stories from writer Michael A. Gonzales, who wrote an essay about Oliver for The Bitter Southerner. In part one of Ursa’s book club episode, they go in-depth on four of Oliver’s short stories: “Key to the City,” “Health Service,” “Traffic Jam,” and “Neighbors.”

Oliver was posthumously awarded the O. Henry Prize in 1967 for “Neighbors,” a story first published in The Sewanee Review about a family grappling with the decision to send their youngest child to be the first to integrate a local elementary school. “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam” were published in 1965 and 1966 by Negro Digest, a magazine founded in 1943 and owned by Johnson Publishing Company, publishers of Ebony and Jet. (Its archives are now available on Google Books.)

In part two, we’ll hear from writer Michael A. Gonzales on what he discovered about Oliver’s life and work, as well as about his own work digging into the archives to put the spotlight on Black writers who never got their due.

On finding out about Diane Oliver and her work:

WALTON: “In her 22 short years on this earth, Diane Oliver was a writer who was just doing the damn thing. She had written six published short stories—published, so who knows how much more she actually had written.

“And just to know that there was someone, a Black woman from the South like us, that had so much promise and had such a career just on the brink, and we lost her, and to know that I’m just finding out about her.”

PHILYAW: “I love reading about Black women, and all the ways that we show up in the world. And it was just heartening to know that in that era, there was this Black woman who thought that the stories of working class Black women deserved to be told, and to be told in a loving way. That doesn’t mean that the characters aren’t flawed, but told in a way that holds them up in their full humanity.”

Content advisory: This episode contains a mention of a racist slur.

Episode Links and Reading List:

- The Short Stories and Too-Short Life of Diane Oliver (Michael A. Gonzales, The Bitter Southerner, 2022)

- “Key to the City” (Red Clay Reader II, 1965)

- “Health Service” (Negro Digest, November 1965)

- “Traffic Jam” (Negro Digest, July 1966)

- “Neighbors” (The Sewanee Review, 1966)

- Diane Oliver obituary (Jet, 1966)

More from Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton:

- The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, by Deesha Philyaw

- The Final Revival of Opal & Nev, by Dawnie Walton

Support Future Episodes of Ursa Short Fiction

Become a Member at ursastory.com/join.

Transcript

Dawnie Walton: The bottom line for me in reading all these stories is that Diane Oliver, again, had so much promise—young, gifted, and Black.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

[music]

Dawnie Walton: Hi, I’m Dawnie Walton.

Deesha Philyaw: And I’m Deesha Philyaw.

Dawnie Walton: And this is the Ursa podcast, where we geek out on all things short fiction. On this podcast, we’ll interview authors, discuss collections and stories we love, and shine a light on new writers and those who never got their due.

Deesha Philyaw: Speaking of which, today we pay tribute to the work of Diane Oliver, who left a legacy for generations of Black women writers coming behind her.

Dawnie Walton: But we’re not just talk, we’re publishers, too. Over at ursastory.com, we’ve created a new home for short fiction from some of today’s most thrilling writers, as well as emerging voices, with stories you can read on your phone and audio stories that you can listen to right here in your favorite podcast app. We’re doing all this, of course, with support from you.

Become an Ursa member today by subscribing in Apple Podcasts or going to ursastory.com/join. And so as Deesha mentioned, today we are paying tribute to the work of Diane Oliver, which is a name that I wasn’t familiar with before we started working on this podcast. But I want to open the conversation with a question for you, Deesha, and the question is: where were you in your writing life by age 22?

Deesha Philyaw: I was nowhere. Well, you know what, I was in the phase where I was having experiences that I would later write about in my writing life. At 22, I got married.

Dawnie Walton: Wow.

Deesha Philyaw: I got married. I mean, gosh, we were way too young, and I was being really practical. I had always enjoyed writing, but I had graduated the year before with a degree in economics from Yale and was looking to do something in business, whatever that was—and crashed and burned there and like nine months.

So at 22, I had gone back to get my master’s in teaching, but I was sort of on the cusp of making this pivot, but writing was nowhere in the mix for me, but I was having these really foundational experiences of figuring out who I was and who I wanted to be in the world, and what would become a marriage that would end in divorce, and all of that later shows up in my writing, but at the time I had no idea what was to come.

Dawnie Walton: I mean, you know, age 22, I was living clear across the country in Portland, Oregon, and also being a practical minded person, working in journalism. I was actually working on the copy desk, reading other people’s writing and having these formative experiences, and whatever writing I did, was probably dedicated to the knuckleheads who were breaking my heart, and like…

Deesha Philyaw: Terrible, for sure.

Dawnie Walton: …Terrible poetry, tortured purple prose, like all of those things. But the reason I asked that question is because in her 22 short years on this earth, Diane Oliver was a writer who was just doing the damn thing. She had written six published short stories—published, so who knows how much more she actually had written. And a little bit of background information about her.

She was a native of the South like us, from Charlotte, North Carolina, grew up Black, middle-class in the 1940s and 50s with all this history sort of unfolding around her, of course, pivotal moment in the United States. Was friends with a student who integrated a high school in Charlotte when she was growing up and would later be inspired by that experience, as well as the regular things about being a young woman in the time.

She went to undergrad at UNC Greensboro, where she published her first short story called, “Key to the City,” in the campus literary magazine, that’s where many of us, I think, got our first publications. And in 1964, she was doing big things, she was selected as a guest editor for Mademoiselle, she got into the Iowa Writers Workshop, she wrote three other stories, all of which we’ll be discussing today, and was a breath away, Deesha, a month away from getting her MFA in the spring of 1966 when she was killed in a motorcycle accident in Iowa City, which has all these alleyways. And that’s how the accident happened. I think a car kind of came out of the alleyway and hadn’t been looking and she was on the back of this motorcycle with someone who was driving the motorcycle and was killed.

She was so close to graduating that she had a thesis on file, which is very—just gave me goosebumps when I found that out. And she was also an activist, which I think inspired a lot of what she wrote about in terms of themes. She did work with Operation Head Start, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC of course, and the Students for a Democratic Society.

And so, just to know, to learn that there was someone, a Black woman from the South like us, that had so much promise and had such a career just on the brink, and we lost her, and to know that I’m just finding out about her in 2021. How did you find out about her, Deesha?

Deesha Philyaw: It was just happenstance, and I’m like you. I’m 50 years old, I’ve been writing for 20 years—never heard of her. And I just want to pause to say, guest editor at Mademoiselle and she was at Iowa. And when we think of these very white literary spaces and the struggles that we have in these spaces now…

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: …To think that she was in those spaces and thriving, but we never heard about it, and obviously, more than likely because of her untimely passing. But it just so happened that this critic and short story writer that I know, Michael Gonzales, reached out and said, “Hey, I’m working on the series on sort of unsung, Black literary heroes. And there’s this woman, Diane Oliver, and ‘Neighbors’ is her most famous, short story.” And I’m like, “What? How most famous? I’ve never heard of her, much less the short story.”

Dawnie Walton: I know.

Deesha Philyaw: And he gave me the biography that you just shared, and I was just stunned that I had never heard of her. But once he gave me the spiel, you know, just the basics, I just knew that I had to tell you about it. I was like, “We have to look at her work and talk about her.”

Dawnie Walton: Yes. I mean, a completely new discovery decades and decades later, and to know that—I think her work had been anthologized by Gloria Naylor, to know the effect that she had on some of those Black women writers that came after her. It was just something that I was really excited to dig into, and we’re going to do a really deep dive here.

We’re going to talk about four of the stories that she published in her lifetime. A warning, because we were going to go deep, there will be spoilers, but we’re going to put into the show notes, links to those stories, so you can read them as well. What was your overall experience kind of discovering these stories and doing that deep dive?

Deesha Philyaw: Her untimely death just loomed over everything, and after each one, I kept thinking, “Where would she, you know, 10 years later, what would the story be?” Because I felt that, when women are at—Black women are at the center of her story, Southern Black women, working class Southern Black women are at the center of her stories.

And the overall feeling I got is that, these were women that were sort of resigned, given whatever circumstances they were in, and I kept wishing—I was like, “I’d love to see when she got to the point of her career where the women resist.” I was waiting for this resistance, like that’s the arc of her talent and her career that I imagined that we missed out on.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, gosh. Yeah, that’s really so many to think about. I was thinking about, there wasn’t a term back then to encapsulate YA, and I feel like a couple of the stories we’re going to talk about, really do that thing that YA does well, which is to present a character who is sort of a young enough to be learning things for the first time and sort of coming to terms with some things in the world, and yet old enough to worry, and that sort of tension between those two things is something that gave the story interest.

And also just seeing her trying to stretch, the other two stories which we’ll talk about, have a protagonist who is sort of a mother of five children and the struggles that she goes through there, which is something that Diane Oliver didn’t have firsthand experience with, but the fact that she was able to sort of stretch that perspective made me think about, you know, like you said, what might have been? What other kinds of perspective she might have tried to explore in her life?

Deesha Philyaw: Because she did something that some writers struggle with, which is—she wrote outside of her own direct experience, but she did it without othering, without pathologizing, without fetishizing. There was such grace and such a knowing and a respectfulness to which she wrote these very human, very complex characters. And that’s a sweet spot that not everybody can hit.

Dawnie Walton: Exactly, that sort of psychological sophistication to be able to do that, so impressive. I just can’t believe she was 22 years old.

Deesha Philyaw: 22.

Dawnie Walton: And wrote, I’m assuming, many of these stories younger than that, because that was the age of her death, so it’s just astonishing.

[music break]

So, moving into each individual story, the first one, we’re going to discuss is: “Key to the City”. This was her first story, she published it by the Art and Literary Magazine of the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and then it was also published by Red Clay Reader.

She used this one, I hear, to apply to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and that’s what got her in. I’m an alum of that program and it’s very stressful, kind of feeling, the confidence to have a story to get in there, it does have a legacy of being very white. And I find myself wondering what her experience was there in that time in history. Where you can read it in full is the Greensboro Reader’s 1968 Collection, we’ll put that in show notes. And that compiled writing from graduates of that program, UNC Greensboro.

And what’s it about? So, it’s the story of Nora. She is freshly graduated from high school in small town Georgia, and Nora has big college dreams and two little sisters, Mattie and Babycake. And the story starts with Nora, sort of imagining Chicago, where she and her mother and her sisters are moving. They’re supposed to be joining the patriarch, who’s already there, kind of getting them set up. They discussed Nora going to a city college and setting her sisters behind her on the same path.

And the story follows north through the family’s preparations for the trip. She’s packing, she’s keeping her sisters in line as their mother finishes up her last shift as a maid, they’re all coordinating with the neighbors who are helping the family move, and holding onto some of their stuff.

And on the trip, on the bus, Babycake gets car sick, and Nora’s mother asks her to ask the bus driver to stop, but the bus driver ignores her. And when the bus suddenly lurches, Nora falls onto a white passenger who calls her basically a “dirty …” and it’s a foreshadowing for disaster in the story.

So, when they arrive at the bus terminal, the father is not there, and Nora calls this number that he’s given and at the number, nobody’s even heard of the father. So, I’m going to read just a small section that is toward the end of the story:

“She tried to brush the hair from her face, but when she removed her fingers they were damp. She stood outside until her eyes were dry.

“Nora went back to the station bench and whispered to her mother who was sitting down quietly. She and Mama agreed—they would spend the night in the terminal, just in case. She watched her mother cover Babycake with a coat, her face turned from Nora as if afraid she might cry. Nora wondered if she had known all the time. Strange that it was morning already, outside the sky was still dark. Later they would call the welfare people, something they’d never done before, and they would find them a place to stay.”

Really upsetting ending.

Deesha Philyaw: And there was the sense of dread that I had from the beginning, and at first, I thought it was that they weren’t going to be able to leave. And so, when they got on the bus, I was Like “Okay.” And so, she built that, she wrote that tension in so wonderful.

Dawnie Walton: Like every moment, there’s a potential for something to go very wrong. I mean, the moment that I can think of, where I felt, “Uh-oh,” is when they are at the bus station and the mother is very carefully counting out the bills for the bus…

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, oh my gosh.

Dawnie Walton: I was like, “Oh no, oh no, they don’t have enough, oh God.”

Deesha Philyaw: And I’m calculating, like, everybody came to see them off, if everybody can give like 50 cents, maybe, you know, like she really created that fear, that stress, she brought us right into just how tenuous their circumstances.

Dawnie Walton: There’s a real eye on money, which is a topic that I don’t think gets enough attention in fiction in general. But Nora has this particular set amount of money that she has herself, like separate from the mother. And throughout the piece, she’s kind of spending a nickel for a popsicle for the sisters, and it’s just very meticulous the way that Diane Oliver sort of tracking each little nickel and Nora understanding that her money is dwindling and being a bit worried about that, which I thought was really interesting.

And yet, in the Georgia scenes, you do have this sense that there’s this community behind them. And so, if something did go wrong you get the sense that the community would help to fill the gap.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s right, but then once they’re in Chicago, it’s the opposite.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: There is no community. And Diane all touches on this in “Traffic Jam,” and then also in “Health Service,” the shame around, the stigma around public aid.

Dawnie Walton: And it’s almost as if the bus trip kind of operates as this bridge between their old and their new life. It starts with such kind of like, wonder and hope, and then there’s the incident with the white passenger that Nora falls on, and then it’s just kind of, like, the baby is car sick, like everything is kind of going wrong and we’re segueing into Chicago.

And I think it’s a commentary as well on this idea that I think some people may erroneously have about the Great Migration, which is that, like, Black people moved from the South and they went to these cities and then everything was free, everything was great, and it’s not quite that way.

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: It wasn’t quite that way, there was still struggle, there was still racism. It may have manifested differently but it was all still there.

Deesha Philyaw: Right. And just how fragile everything was, all it took was that—obviously, it’s not a small thing, but the father not showing up and meeting them. But you see it from the perspective of people on the outside looking in. It’s like, “Well, here’s this woman with all these children.”

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: And then there’s the lens of pathology and so forth when there’s a whole backstory there. So, there are systems at work, but then there’s this family’s personal story, and it all hinged on this one man, doing what he said he was going to do, but he didn’t.

Dawnie Walton: You’re right.

Deesha Philyaw: And then their faiths are forever changed. And when you were talking about the bridge, it made me think about how she opens the story, which is the chicken, the roosters, and she can hear them and she can see them. And they’ve had these chickens since they, you know, their family has lived in the house for however long. And then before they leave, they eat the chickens.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: And that also kind of gave me the sense of there’s no turning back.

Dawnie Walton: Wow.

Deesha Philyaw: That it’s something—something is going to be lost, but at the time, we didn’t know what it was.

Dawnie Walton: I also found this interesting: There was a small moment, where Nora is—I think she is either talking to, or thinking about an old classmate of hers named Jimmy. And she’s talking about how Jimmy kind of stopped messing with her, talking to her when she topped him on a test or in a class or something like that.

And I think that’s something that Diane Oliver also is doing in her work is sort of talking about these gender dynamics, and kind of about male ego, which we see quite a bit of in “Traffic Jam.” And so, it’s all very complex and interesting, but the ending was sort of a punch in the gut.

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: And again, as you said earlier, it hints at that kind of note of resignation, you know, the way this story ends, there’s a couple more paragraphs after what I read, and it’s basically Nora going into logistical mode, the same as she had been packing earlier and getting her sisters ready. It’s like, “Okay, so tomorrow I’m going to call this person and I’m going to do that thing.” And it’s like, you can feel all her college dream just….

Deesha Philyaw: Just slipping away.

Dawnie Walton: Just slipping away.

Deesha Philyaw: Because she has to spend money to make that phone call, so it’s like, we’re starting to count down again.

Dawnie Walton: There’s so much meaning in those details, in that caretaking work that the women do in the little decisions, the tiny choices that they make every day. You know, the fact that the mother has to basically work overnight and then kills the chickens and Nora wakes up to the smell of her frying them, so they’ll have something to eat on the bus. Like, all these things, it’s the small details that show what it was to negotiate those times. So, as you said, I mean, I think there’s so many similar themes in the next two stories

Deesha Philyaw: Yes. So, the next two that we read, they’re really companion stories. They are—the titles are: “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam.” And “Health Service” was published in November 1965 in Negro Digest, which is a magazine that was owned by a Johnson Publishing Company, the publishers of Ebony and Jet. And I think Diane Oliver was going to have an internship with them upon graduation.

Dawnie Walton: She was. And can we also just pay tribute to the moment where magazines like this published fiction?

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: I mean, do you remember when Essence used to publish fiction, they had a fiction contest?

Deesha Philyaw: I do, and they stopped. I remember reading my mother’s Essence magazine as a child, and I remember this short story with a—featured a Black woman, and it was the scene with her putting talcum powder on her breasts.

Dawnie Walton: Oh.

Deesha Philyaw: And that was like the Blackest thing I ever read in a magazine. And then I don’t remember any stories in Essence after that. What’s that about?

Dawnie Walton: I don’t know. It makes me so sad because I remember they would also excerpt books that were coming out that you were so excited about. And I think I remember reading kind of one of the sexier excerpts from Disappearing Acts in Essence.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: And I was like, “Ooh”

Deesha Philyaw: Shout out to Terry McMillan.

Dawnie Walton: Sorry, went on a tangent.

Deesha Philyaw: Let’s meet in “Health Service.” Oliver revisits those characters later in the story called “Traffic Jam,” which Negro Digest published two months after her death in July 1966. The archives of Negro Digest are freely available on Google Books. So, listeners, you can read it there, we’re also going to drop a link in the show notes for that, those stories as well.

So, just to give you a little background about each story, and then we’ll talk about both of them. In “Health Service,” we meet Libby, who is a young Black mother of five young children, and they range in age from infancy to just about to start school, kindergarten or first grade. So they’re really close in age.

And when we enter the story, she’s walking with the children on a hot day to take them to get their shots, and she’s not sure which shots they’re supposed to have, but she figures that the people at the health clinic will know. And the irony of the title here, “Health Service,” is that Libby and the other Black folks who are waiting to be seen at the clinic don’t actually receive good service, and in some cases, they don’t receive service at all.

Libby and her children are scolded by the white nurse who repeatedly refers to them as “You people.” Everyone at the clinic is at the mercy of this nurse, and she represents this larger system of lack of care.

And so, in the moment though, Libby is struggling to wrangle her children who are understandably restless and bickering during this long wait, and Libby begins to anticipate their hunger as the day drags on, and she can’t afford to feed them anything from the vending machine.

So, she’s struggling to hold her little family together, she’s also struggling to hold herself together because she’s parenting alone. Her husband, Hal, has disappeared extensively to find work, but he hasn’t kept in touch and Libby doesn’t actually know where he is.

At this point, she refuses to apply for welfare and she frets over her children being unkempt in public. So, she’s very proud, but she’s juggling more than anyone should have to bear alone. So, the excerpt I’d like to read is actually from the end of the story where—spoiler alert, they’ve endured all of this, but they don’t actually get their shots, they don’t actually get service that day. And so, Libby and the children have left the clinic.

“For an instant, Libby thought about keeping straight up the main street and walking around the shopping center. She hadn’t been window shopping in ages, but keeping up with her children wasn’t worth the trouble of seeing new clothes. Besides, it was way past time for them to eat, and the sooner they passed somebody’s peach tree the better. She shifted the baby to the other arm, caught hold of Wicker, who was walking slower than anyone else, and started home.”

So, there’s just—oh my goodness, this kind of wistfulness, and again, that sense of resignation for her, for his young mother.

Dawnie Walton: And I just, you know, I feel this is a story that could be written today, unfortunately, with the state of our healthcare system…

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: It could be written in any emergency room or urgent care clinic. And it’s just kind of heartbreaking, and the fact that what you said about her anticipating the children’s hunger, like they’re not even hungry yet, but knowing that that’s coming and those small, mundane concerns that you have all the time, just how big they can loom for this young woman.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes. And Diane Oliver was just a master at capturing the everyday and the mundane and those details that are small, but that speak volumes. And I remember thinking, “How did she know?” Because as we mentioned, she’s writing about experiences that are not hers, and I thought, well, maybe working at Head Start or even just family members and observation. So, what this tells me about her is that she was a keen observer of people, and a sensitive observer of people for those kinds of very resonant, small details to show up so powerfully in her fiction.

Dawnie Walton: And as awful as that nurse is, there is a character that brought me a lot of joy, and that was a secondary character named Mrs. Courts in “Health Service,” who was in an older elderly Black woman who just very simply offers to watch the kids while Libby takes one to the bathroom, she’s just kind of there to sort of stand in that gap when Libby needs that help.

And she’s very empathetic toward her, which I thought was a beautiful thing. And, as the nurses, they stand in for the larger idea of the health service, Mrs. Courts is sort of the stand in, I think, for the community.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes. And you know, you saying that made me think how all four of these stories that we’re going to talk about, they all in a way could have been called “Neighbors.” It’s how our neighbors or how the neighbors in these stories, how the community does and doesn’t show up for each other, and how the community shows up. And then when we are forced as Black folks to rely on the state, what does that look like?

So, we meet Libby again in a story called “Traffic Jam,” and a little bit of time has passed — her oldest child has started school and while Libby works, the next three oldest kids stay with Libby’s mother, who we understand from both stories is in failing health.

And then the baby, Calvin, stays with a neighbor, Mrs. Dickinson, and where Mrs. Courts in “Health Service” was helpful and kind, Mrs. Dickinson—I would like square up with Mrs. Dickinson because she’s a neighbor who forces Libby to leave her baby unattended in a laundry basket on the front porch each morning, as she’s on her way to work, she won’t let Libby leave Calvin inside the house.

She tells her that “6:30 was too early to be fooling with a baby.” And also “Besides, everybody around here has got too many babies to have to steal one off of my porch,” which is ridiculous. But there’s again a little bit of social commentary there that people are having too many children. This is a perspective that Mrs. Dickinson has, and she uses that to rationalize that harm won’t come to this baby on her porch.

Dawnie Walton: Which is wow.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, Libby has to leave her baby unattended and then go and work at the home of Mrs. Nelson, her employer. So, Mrs. Dickinson is cruel to Libby in this way, but Libby’s boss, a white woman named Mrs. Nelson, is even worse. She insults Libby, she talks down on Hal, who is Libby’s absentee husband, and only gives Libby food to take home once it’s spoiled.

Dawnie Walton: Them cookies — the cookies that were too burnt up.

Deesha Philyaw: Bits. Like, literally, I’m going to give you things that aren’t fit for other people to eat, but this is sufficient for you and your children….

Dawnie Walton: And take that and be grateful.

Deesha Philyaw: Right, yes, she expects so much gratitude from Libby. And I had said earlier that I wanted to—one of the great losses of Diane Oliver dying so young and so early in her career was that we didn’t get to see what I think would be some more resistance from her women characters, but we see it here. We see the roots of it here. Libby sneaks away, she sneaks and washes her family’s laundry when Ms. Nelson is away and Libby takes fresh food that she thinks that Mrs. Nelson won’t miss.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: So, she’s pushing back in that way. Mrs. Nelson is pressuring Libby to arrive earlier than scheduled. So, she already has to drop off her baby at 6:30 and leave the baby unattended, Mrs. Nelson wants her to come even earlier than that. And she routinely expects her to stay and work late.

So, in the occasion of the story, this particular evening as Libby is leaving work late, Hal, the missing husband appears and Libby is both happy to see him and furious with him. He’s come home with a new car that he expects Libby to be excited about. Again, I wanted to square up with Hal.

Dawnie Walton: Okay?!?

Deesha Philyaw: Right? It’s said understandably Libby isn’t excited about this car, she can only think about how they won’t be able to afford gas for the car and how her children are practically starving. Hal is not only oblivious to all of this, but he has the nerve to be critical of Libby’s parenting and even violent towards her, before the story ends.

And this is one of my favorite stories of the four we read, and it was in part because I had such an emotional, deeper emotional reaction to it, particularly this last scene. And she writes:

“The starting motor interrupted her thoughts and then Hal was talking.

‘I said did you want to stop by your mama’s before we go home?’

She did not answer. He seemed to have a knack for making her do things she never planned on doing, but if she wanted him she had to want the car. There wasn’t any sense in even thinking about fixing up the house. Now all their extra money would go for gas. But at least he had come back to her, and somehow nothing else was very important. She settled back into the seat, her eyes drawn to the profile of his head—the hair closely cut, his eyes so intent on the road that if she would not have known better, she would have expected traffic miraculously to appear.”

Dawnie Walton: That one line, “If she wanted him, she had to want the car.” That is my favorite sentence in all of the stories that we read, because it is just so…It knocked me out. I was like, “It’s true.” It’s so true for this story. It’s such a keen observation of these characters, this couple and the relationship between them, and it’s just heartbreaking that Libby doesn’t—she doesn’t quite have the capacity to dream a little better than that, you know, than—I don’t know.

She wants the father for her children, of course, and in order to keep him around and appease him, she has to show this excitement about the car, even though it’s going to become a burden, she knows the burden that the car already is, right?

And it’s just, in some ways you empathize with Hal as well, because this car is sort of symbolic of something for him, it’s meaningful to him in some way to come back and to have this very kind of symbol of where he’s at, and how he’s doing and how he’s been and kind of, in his mind, it’s supposed to quiet all those questions and it’s just—but the questions are still there.

Deesha Philyaw: And so are his children,

Dawnie Walton: So are his children.

Deesha Philyaw: Who he wants to have candy, but meanwhile, they don’t have actual food to eat. And the sense of dread that I had when she said the part about wanting him, it triggered this thought that—and she’s going to have another baby, because you know, what’s coming next.

And again, like how def…I can’t say the word “deftly,” that Diane Oliver created that. She’s got us worrying about things that haven’t even happened yet, but we know what’s on the horizon for this character. And we’ve seen that she can resist in some ways, but will she resist against him?

Dawnie Walton: And I think as devastating as the stories end, there’s also a brilliance in the endings in the sense that—something that helps me to write my own endings is to not think of an ending as closed, but to sort of think of… the ending opening up a whole new beginning ino another story.

And I feel like, just like you said, we know what’s coming next, they’re probably going to have another baby. You know what I mean? That the fact that you can imagine that you’re thinking about what comes next for these characters, is sort of the brilliance of the endings. And I think the same is true in “Key to the City.”

You can kind of think about what’s going to happen to these characters in Chicago. Now that they’re on welfare, you can think about their living circumstances, all of these things.

Deesha Philyaw: And when you mentioned “Key to the City,” it makes me think about—and I don’t think the word was tossed around during Diane Oliver’s time: “respectability.” Because both Libby and the mother in “Key to the City” are married women, right? And so, marriage is supposed to convey respectability.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: But based on the actions or failures of the men they’re married to, they become women who lose respectability. In Libby’s case, he marries her, but he doesn’t give her a ring.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, her mother slips a ring on her finger so that she’s not treated poorly at the hospital, or she’s not viewed as an unwed mother in the hospital and really married. And so, both Libby and the mother in “Key to the City,” have large families, they have a lot of children and they are essentially raising them alone. And so, we know the stigma that comes with single motherhood.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, I think Diane Oliver is doing something really interesting here by saying, “But these are women who… they follow the rules.”

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: They did things the way that society tells them to, in order to have that respectability, and yet, it isn’t something that they can actually hold onto, it can be taken away from them by no fault of their own. And so, I hope for people it would sort of call into question why we invest anything in the idea of respectability for lots of reasons, but one, it’s so flimsy.

Dawnie Walton: You just reminded me of the beginning of “Health Service,” when Libby is walking to the clinic and they stop, and she runs into, I think, an old friend of her and Hal, and he’s sort of shaking his head at her, and it’s just so much judgment all the time. And you’re really able, through Diane Oliver’s writing, to sort of feel what that judgment must’ve been like and to empathize so much with these young women.

Deesha Philyaw: And we think that question comes up a little bit in a very subtle way in the last story, “Neighbors,” right?

Dawnie Walton: Yes. So “Neighbors” I think is probably Diane Oliver’s most well-known story, for those who know her, and probably most directly engaging with politics and social issues. It’s a little less subtle, I think, than the other stories.

It was published in the spring of 1966 by The Sewanee Review, published right around the time of her death, and in it, she draws on that friendship with the first Black student who attend all-white Harding High School in her hometown of Charlotte.

It’s included in Short Stories of the Civil Rights Movement, which is available via Google Books. And in “Neighbors,” we meet Ellie, we meet her on a city bus. She’s coming home from her new, full-time job, so we’re never directly told her age, but I peg it around maybe 19, 20. And on the bus, she glances at a newspaper and she wonders if her family will be in the headlines again, as they had been when Ellie took a character, little Tommy, to get his polio shot for school.

So we get the sense that she’s a caretaker in some sense of this little boy, and something about his schooling is newsworthy. And so, Ellie dawdles when she gets off the bus, she’s window shopping, she runs into a couple who tells her they have the family’s back and to be careful out there. So again, we have this dread building, not quite sure yet what’s going on, but are kind of putting the pieces together.

And Ellie also runs into a friend of her Saraline, who is hanging out with her boyfriend, and there’s some kind of silent understanding I feel between Ellie and Saraline, and so on her walk home, Ellie stops by Saraline’s house and lies to her grandfather that she’s working late.

And the grandfather asked Ellie if her family is ready, if they’re going to let Tommy go tomorrow. And so, I think by this time I was pretty well aware what was happening. Little Tommy and the family is supposed to go to his first day of school tomorrow, and he’s the first Black child to integrate this school. And I think Diane Oliver gives the school the name Jefferson Davis, which, I mean, is familiar.

Deesha Philyaw: We grew up…

Dawnie Walton: You and I grew up in Jacksonville, where my neighborhood school that I was zoned for — it was Robert E. Lee High.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s right.

Dawnie Walton: Just recently changed its name to Riverside High, but there were all kinds of…There was a Jefferson Davis, right, in Jacksonville?

Deesha Philyaw: Was it that, or was it Jeb Stuart? Because I was thinking that, but I think I might be conflating it with Jeb Stuart.

Dawnie Walton: And there was another one for the…The most egregious one, I think was the KKK Wizard, I forget what his…Anyway.

Deesha Philyaw: Right? Because the newspaper did a whole article about it.

Dawnie Walton: Listen, so that detail really hit home for me. So anyway, so the front part of “Neighbors” is a lot of foreshadowing about this family grappling with the decision of whether they’re sending Tommy into what is essentially a war with desegregation, and when Ellie gets home, there are several men in the house who are meeting with her father and there’s her very anxious mother kind of bustling around, and Tommy is in the back room and he seems afraid and uncharacteristically quiet.

And there’s many ominous cars, including police cruisers, circling their house. And as Ellie observes everything around her and helps her mother and gives Tommy a bath and tries to reassure him about the next day, we learned, of course, that the family has been getting threats, as would happen.

And Ellie discusses with her parents whether they should send Tommy and suddenly, a bomb is thrown toward the house and it hits the front porch, it misses a more direct hit, and so it’s kind of a close call. The family is shaken, the cops show up. Tommy, who suffered a cut on his face, is sent to bed, but nobody of course in the family can sleep.

And the last few pages of the story are set in the kitchen, a very tense scene with Ellie watching her mother and her father finally making this decision about Tommy’s fate. And so, I’m going to read an excerpt from the end of that story. This is the parents talking:

“Jim,” she said, sounding very timid, “what we going to do?” Yet as Ellie turned toward her she noticed her mother’s face was strangely calm as she looked down on her husband.

Ellie continued standing by the door listening to them talk. Nobody asked the question to which they all wanted an answer. “I keep thinking,” her father said finally, “that the policemen will be with him all day. They couldn’t hurt him inside the school building without getting some of their own kind.”

“But he’ll be in there all by himself,” her mother said softly. “A hundred policemen can’t be a little boy’s only friends.”

She watched her father wrap his calloused hands, still splotched with machine oil, around the salt shaker on the table.

“I keep trying,” he said to her, “to tell myself that somebody’s got to be the first one and then I just think how quiet he’s been all week.”

Ellie listened to the quiet voices that seemed to be a room apart from her. In the back of her mind she could hear phrases of a hymn her grandmother used to sing, something about trouble, her being born for trouble.

“Jim, I cannot let my baby go.” Her mother’s words, although quiet, were carefully pronounced.”

And the mother does have the last word: They decide not to send Tommy. And then as in most of these Diane Oliver stories we’ve read, the ending kind of begins with the mundane again, with Ellie helping her mother make the oatmeal for when Tommy wakes up.

So, there’s a lot going on in this story. And this is the story where for me, I felt the point of view was incredibly effective because we have Ellie kind of operating as an observer, right?

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: And kind of grappling with how she feels, but without being the character in the position of making the decision, but of course, having opinions on the decision and being old enough to understand the stakes and old enough to have worries for Tommy. So, I thought that was like the choice of character through which to view this story, I thought was really great. And a character that was close in age, I feel, to Diane Oliver herself, you know?

Deesha Philyaw: Well, I struggled with that, and I struggled because I kept thinking that Ellie was Tommy’s mother, his biological mother and not his sister. And for two reasons in the story, there’s one where she notes that he looks just like his father, but if they were siblings, then she would have said our father.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: There was one. And then when the mother is—when Ellie arrives and the mother’s sort of saying where everyone is. She’s saying, “Some other siblings are with one neighbor set of neighbors,” and then she says, “Your brother is staying elsewhere,” and then she says, “and Tommy is in the back.” And that suggests to me that Tommy is not Ellie’s brother.

And so, in terms of point of view, if this a child that Ellie gave birth to—and we know that in the community during that time, it was not unheard of—that if a young woman had a child unmarried, for that child to be raised as a sibling and that child never knew, everybody else might know. We know of circumstances like that. I thought that that was what was happening here and just like it was unspoken in the story.

Dawnie Walton: In the story.

Deesha Philyaw: But I wanted something to suggest that, Ellie might’ve felt she had more of a say over what happened with Tommy, because she did give birth to him.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: Or if she was fully relinquishing all rights in that way that we would have heard that too, but it was so unspoken, what I’m suspecting, that it left me confused and it distracted me from the story and…. yeah.

Dawnie Walton: You and I discussed this in kind of our notes on this show. And I will say on first read, I was very confused about the relationships in the family, because although there are many moments where we get into Ellie’s head, there’s a distance there as well. There’s always like, her mother, his —instead of fear, or there’s one moment where it’s like, “the woman addressed the girl” or something. It’s just so many strange moments of distance.

And one of the things I said that we should discuss is as promising and brilliant as Diane Oliver was, you know, the truth of the matter is she still had room for growth, and that’s part of the beauty of her story as well, is that you can see kind of those things that you know she would have kind of clarified.

I’m still not sure if she was meant to be the sister or the mother. I think there’s arguments for both throughout, but I guess my question would be, is that intriguing? Does it add another layer for you? Or is it just unexplored and frustrating?

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah. And I think that’s something we’re always grappling with as writers is, how do we want to use ambiguity? Does it serve to allow the reader to bring themselves in their experiences and their biases and fear? Is it creating space for the reader to make meaning and develop understanding? Or is it just a source of confusion? And that could be a fine line. And I am going to say something maybe a little inflammatory, but this was published in Sewanee Review. The other stories we read, one was published at UNC Greensboro, but the two that were published in Negro Digest, I felt were her strongest.

Dawnie Walton: I agree.

Deesha Philyaw: And I wonder if she was facing with Sewanee Review what we sometimes face, is that there’s so much emphasis from white editors on the politics of what we’re writing about and not the craft, not our craft. So, I could be totally off base with that, that could be a totally unfair thing to say that happened, but that’s just my—I’m wondering if that’s what happened.

Dawnie Walton: I want to get back to that, but I want to back up a second to something that you said about that ambiguity that we sort of grapple with, you know, how mysterious to be in moments. And I think as young writers, you know, when was first starting, I think that we have this concept of the ambiguity being the brilliance somehow — that if we make it opaque and difficult to understand that it feels sophisticated.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s “literary.”

Dawnie Walton: That’s literary, you know what I mean? And it takes a while to get out of that way of thinking and just to make things plain and clear, and just fully explore them—that ends up being more satisfying.

So this is the story that is of course most directly political. It’s got an intersection of real history into the fictional world. How do you feel about work that does that? Especially this particular story is written very close I think to real history, to those events. And I often in my work integrate real history, but I get nervous when it’s too close to the moment because I feel I don’t yet have the proper perspective to really write about it in a way that feels resonant. And I’m just curious to hear your thoughts about that.

Deesha Philyaw: I always worry because I don’t want my writing to ever be too on the nose. And one of the many beautiful things about your novel is that, it was not on the nose, that the history was the backdrop. It was certainly important, but it was the characters, it was their voices, it was their stories, it was their messiness that had me riveted, but we got that history too. And that history was important. Without that history, you don’t have the same story.

So, the history mattered, but you trusted us as readers that you didn’t have to beat us over the head with the history that it was just woven very organically into the character’s stories, and that’s what I like, and that’s what I try to do. I don’t want to be didactic, I don’t want to be hamfisted, I don’t want people to see, you know, this is where Deesha did her research.

Dawnie Walton: Right. You don’t want to see those seams.

Deesha Philyaw: Right. I know that your book was heavily researched, but I didn’t see the seams, it was that seamlessness that I think we’re going for.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, thank you.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh, thank you.

Dawnie Walton: Well, it’s always a question that you hold in the back of your mind: how to write about these things without being didactic. And I do wonder how successful this story was at doing that. I mean, I think that there are things that happen that are a little on the nose, the bomb being thrown and all those things. And at the end, you kind of almost have a philosophical conversation between the mother and the father. And yet, I think she does inject some emotion, especially watching the mother character and sort of her resoluteness in the decision. But it’s a really difficult balance to strike.

Deesha Philyaw: It also raises questions, I think, around gaze, and this could have to do with who were her editors for these different stories? But we were literally inside of a Black family’s home, and there wasn’t the intimacy. And I don’t mean intimacy in the sense that the characters should have been more lovey-dovey or warm towards each other, because I think their lack of intimacy also said something about their relationship with each other, like what kind of folks they were.

But I don’t know, I just felt like, you know, when I’m reading… I guess I just am so used to reading situations like that, where if it’s really our gaze, it feels more familiar. And the other stories and the other characters felt familiar. These characters felt very distant and unfamiliar and kind of stilted, but again, that could be… this is who those folks are, but I don’t know, something—it just didn’t curl all the way over for me.

Dawnie Walton: It’s interesting to think about what you just said, maybe that’s what these characters were. I mean, the family that is chosen, I guess, to be the family to go through this. That’s kind of interesting to think about what a family like that would need to be like in order to sort of be representative and respectable and all of those things. So, that’s interesting to ponder.

Deesha Philyaw: It kind of reminds me of the story of, you know, why was Jackie Robinson chosen, because he was not going to fight back physically. And so, that would make total sense that this family was chosen for a particular reason. But I really found myself wanting maybe a counterpoint to that. Like one of them—I mean, and the parents had a subtle disagreement, but somebody to be like a bigger counterpoint. I don’t know, it’s like, you know, fiction life is more dramatic than real life. That felt so on the nose and just subtle as opposed to creating more conflict. There was a lot of conflict left on the cutting room floor, it felt like, to me. There was a lot of potential.

Dawnie Walton: Well, I just read for the first time Song of Solomon, and do you know that scene where Milkman and Guitar are sort of having this philosophical conversation about—not civil rights, per se, but about like what the community needs to do, and I thought that you just made me think about that, and how charged and kind of messy that dialogue is, and thus how real it feels, and how kind of provocative it feels.

And it’s not the same here, but it just made me think about how as writers, we want to kind of craft those moments of dialogue where the dialogue is trying to do so much, it’s trying to show these two sides of an argument while also revealing character and being propulsive, and putting all that effort into that dialogue.

Deesha Philyaw: Right. And it’s like, what’s at stake? And so on the surface, what was at stake was this child’s life, but we don’t get to see them go to school. So there’s got to be some emotional stakes, because you kind of diffused, you know, Diane Oliver in the choice that she made in terms of how it ended, you sort of diffused that moment.

And honestly, I read that several times and I wasn’t entirely convinced that they weren’t going to send him, It was so unclear, but things they actually said, Yes, it makes you think that, Okay, they’re not going to send him. But again, everything was so muted, there wasn’t that clarity, but if he’s not going to go, what’s at stake? And the end, there was no secondary conflict or stakes, emotional stakes between any of the characters.

I thought there was a potential there because one—especially if we thought that perhaps Ellie was Tommy’s mother, but what did you think about how when she spoke to her father, when the door was locked? I felt she was pretty bold, she’s kind of impatient, you know, she can’t get in the door, and it was just…

Dawnie Walton: Oh, right. When she first comes home and he’s like, “It’s open.” And she’s like, “I told you, it’s not,” or something. I’m like, “Ooh,”

Deesha Philyaw: Spicy.

Dawnie Walton: Who talks to their daddy like that?

Deesha Philyaw: So, I thought, “Here we go, something’s there.” And it just—it wasn’t, though.

Dawnie Walton: Right. When I did secondary reads of this story, I asked of the story, a question that I often ask myself as a writer, because I often struggle with this. And the question is, does this story begin in the right place?

Deesha Philyaw: Ooh, yes. I had the same question.

Dawnie Walton: What do you think about that?

Deesha Philyaw: I had the same thought because I was like, I wanted to see this whole thing about the one set of “Neighbors” where they decided not to send their child, you know, because right there, there was some conflict, could one set of parents confront the others and say, “Let’s send our kids together.”

I don’t know. And then the question of Tommy being Ellie’s son. So, I wanted to see more there. Was there a moment where Ellie tried to weigh in and her parents said, “This is not your call to make.”

Dawnie Walton: Right. You get all these pages and pages of Ellie on the bus and her slow walk home. And I think we’re meant to be learning about Ellie as a young woman, and yet, this question of whether she’s Tommy’s mother or sister, is still a little unclear, and it’s just kind of lacking the tension that such high stakes would require, I think.

Deesha Philyaw: And again, I wonder if it was like a white editor thing, like, “Ooh, we have a moment where the young Black woman is on the back of the bus.” I mean, we would be like, “So? And…?” That doesn’t tell us anything, it’s 1964, you know? So again, whose gaze was driving some of the editorial choices that she was making here?

Dawnie Walton: And we say all this and I look back at my 22-year-old self and think I could never…

Deesha Philyaw: Oh God.

Dawnie Walton: …write something that has so much promise.

Deesha Philyaw: No.

Dawnie Walton: And the fact that we’re discussing it at this level, you know what I mean? Like, it just….

Deesha Philyaw: My early fiction was everybody had to end up in church at the end. So, I’m not wanting to talk about nuance or where the story starts.

Dawnie Walton: But the bottom line for me in reading all these stories is that: Diane Oliver, again, had so much promise – young, gifted, and Black. And, I found myself thinking about where she would have gone in her fiction. Especially with her activist work…

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: … And her fiction writing kind of dovetailing, and as… movements sort of evolved, how she would have evolved as a writer.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, so much promise, so much promise.

Dawnie Walton: Any other final thoughts you have on what these stories sort of reinforced for you or taught you?

Deesha Philyaw: Just how much I love reading about Black women, and all the ways that we show up in the world. And it was just heartening to know that in that era, there was this Black woman who thought that the stories of working class Black women deserved to be told, and to be told in a loving way. That doesn’t mean that the characters aren’t flawed, but in told in a way that holds them up in their full humanity.

You know, I’m always down to see that, and so to know that it was happening, at that point, and it made me hungry for more, you know? And Negro Digest, I feel like I could fall into those archives now.

Dawnie Walton: Yes, absolutely. Now that I know that they are freely available on Google Books, I want to go back and see all the fiction that…

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: …they might’ve published. And I was thinking about where I see or hear echoes of Diane Oliver’s voice. And I feel like there are so many YA writers who are sort of doing a version of what she’s doing with “Neighbors,” you know, Angie Thomas writing very politically, but also on a deep character level.

But I also think about books like Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson, and getting even more evolved and sophisticated in the complication of the characters and the situations that they’re facing. So, this was a really beautiful thing, to be exposed finally to these stories.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes. So, shout out to Michael Gonzales, @gonzomike, for…

Dawnie Walton: Shout out!

Deesha Philyaw: …hipping us to Diane Oliver.

Dawnie Walton: And thanks for joining us today. If you enjoyed today’s conversation and want more, become an Ursa member by subscribing in Apple Podcasts, or by going to ursastory.com. You’ll help us produce our original stories and you’ll support our work on this podcast, as we turn you on to our favorite writers and short stories. You can also support this podcast by leaving a review and a comment in Apple Podcasts. Until next time, talk to you later, Deesha.

Deesha Philyaw: Take care, Dawnie.