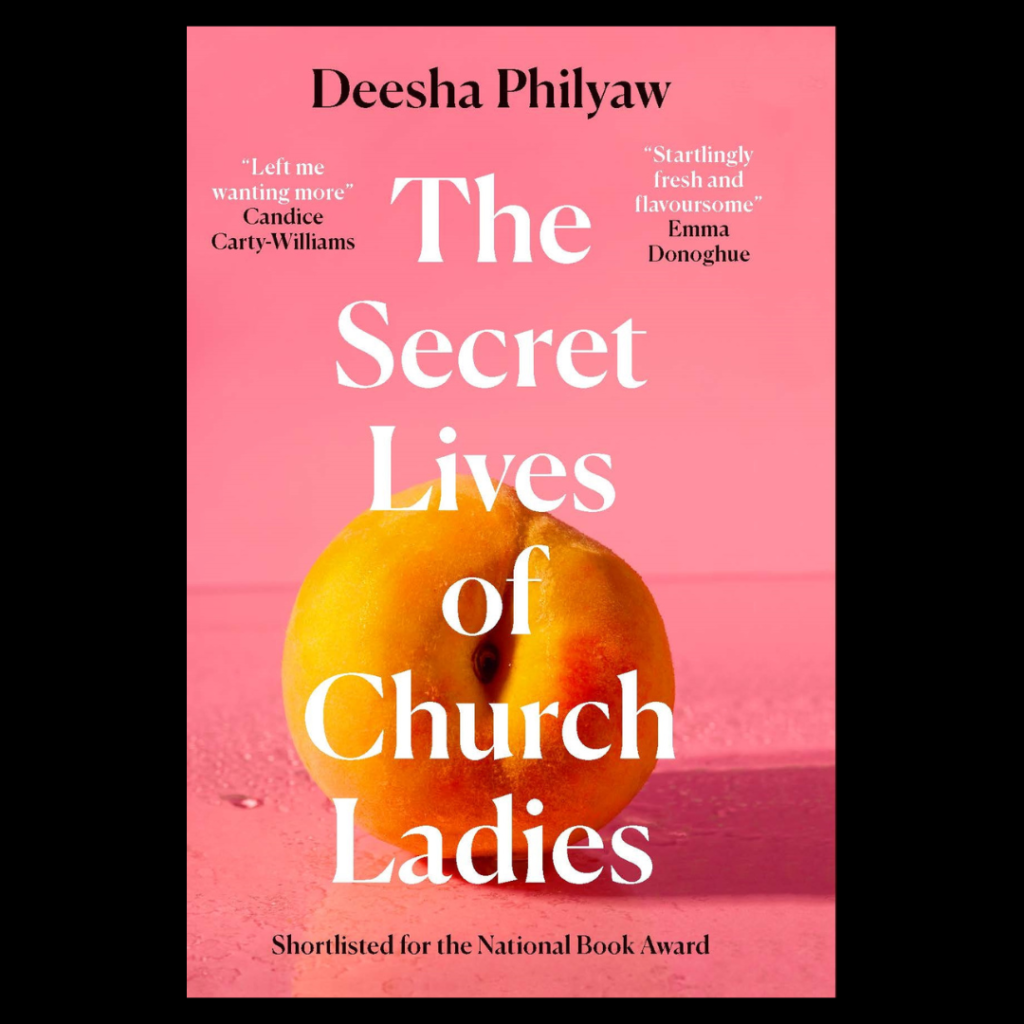

This month marked the two-year anniversary of the publication of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, author Deesha Philyaw’s groundbreaking and award-winning debut short story collection that examined the inner lives of Black women as they navigate relationships, sex, and the church.

On Episode 14 of Ursa Short Fiction, Dawnie Walton digs into the stories with her co-host Philyaw, and gets some hints on what might be in store for the characters as Philyaw and Tessa Thompson are adapting The Secret Lives of Church Ladies for HBO Max.

Philyaw’s collection won the 2021 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the 2020/2021 Story Prize, and the 2020 LA Times Book Prize: The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction and was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction. Philyaw is a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow and the 2022-2023 John and Renée Grisham Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi.

This episode was edited by Kelly Araja.

Author photo by Vanessa German.

From Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton:

- The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, by Deesha Philyaw

- The Final Revival of Opal & Nev, by Dawnie Walton

Support Future Episodes of Ursa Short Fiction

Become a Member at ursastory.com/join.

Transcript

Deesha Philyaw: What I’ve heard from more than one person, which I think is hilarious, is they will send this book to, like their mother or their churchiest auntie with no explanation. So, the first thing you would read is “Eula.” And so, they then will text or call the person that gave them the book, usually another Black woman and be like, “What is this?”

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: Hi, Deesha.

Deesha Philyaw: Hi, Dawnie.

Dawnie Walton: Well, today is a very exciting day for the Ursa podcast, because this is the day I’ve been waiting for. We are going deep on a little short story collection that you may have heard of before; it is called The Secret Lives of Church Ladies.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh, I’m so excited.

Dawnie Walton: Oh my gosh. You are excited. I’m excited because I just reread this beautiful collection for the third time over the weekend. And I don’t know what I’m going to say except basically gush.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh my gosh.

Dawnie Walton: But, you know, this book has been out now for two years, first published by West Virginia university press in 2020. And this is a game-changing short story collection, but we’re going to let the numerous awards and accolades speak for themselves.

So, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies was a finalist for The National Book Award in 2020, it won the PEN/Faulkner Award 2021, won The Story Prize 2020, also the winner of The LA Times Book Prize, The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, and now coming soon to HBO Max in a dramatic series produced by Tessa Thompson. How amazing is that? So excited.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: And so, today we’re going to dig into everything about this collection with Deesha, how she first came up with the idea and the initial stories and we’re going to go down to the sentence level on the stories that stuck with me, meaning all of them. So, please consider this a spoiler alert. We’re going to be talking about Tasheta. We’re going to be talking about “Peach Cobbler”…

Deesha Philyaw: My girl.

Dawnie Walton: We’re going to be talking about Jael, all of it, everybody—so excited. First, some quick housekeeping. If you’d like to support our show, leave us a five-star review and comment on Apple Podcasts. You can also help us fund our next season of interviews and stories by going to ursastory.com/join or subscribing right inside the Apple Podcasts. Now we’re about to go in.

Deesha Philyaw: Let’s go, let’s go.

Dawnie Walton: Okay, so this is a story that I have heard a few times now, but for those who are listening that need a little bit of inspiration who love the short story form, aren’t sure about how short story collections perform, how they get out there, how do they get to agents, all of that stuff. Can you talk about the backstory of this collection and how it came to be published?

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, so Church Ladies was born because I was trying to write a novel—trying unsuccessfully to write a novel. It’s a novel I’ve been working on since 2007. And in the meantime, I co-wrote a nonfiction book with my ex-husband, a book on co-parenting and that’s how we got an agent. And my agent has been saying to me since 2013, when the co-parenting book came out, “When that novel’s ready, I’m ready for it.”

And the novel, to date, still is not ready. But what I was doing more so than working on that novel or when I would kind of stall on the novel, I would have started writing short stories. And, there were two that my agent had read and heard me read at events and so she had this idea that while I was on what she called hiatus from the novel, I just called it not working on it, that I could pivot and make a collection, build a collection around these short stories.

And she saw themes running through that I hadn’t thought about thematically because I hadn’t thought about the stories thematically because I wasn’t thinking about a collection but around Black women, sex and the Black church, and once she said it, and once she referred to them as church lady stories, I was very interested in that, and I was like, Yeah, that feels more doable than this book that I’ve been stuck on for so long. Not because writing short stories or building a collection is easy, not by any stretch, but I could see a clearer path than I could with the novel where I was just in over my head.

And so, I got intentional about these stories and how they could come together. And what else could I write that could help form this cohesive collection? And then my agent is a Virgo like I am, so she got very specific and she said, “When you publish three of them, we’ll have the basis, we’ll have a partial manuscript, and we could go to market with that and try and get a book deal.” And so, I was like, okay. Like, I was that kid in school that liked homework, you and I went to a high school that was for kids that liked homework.

Dawnie Walton: Let me tell you our high school was harder than college for me.

Deesha Philyaw: It was!

Dawnie Walton: It was, and my mother would worry about me with all the books that we had to carry in our book bags.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, yes. So, you tell me, give me an assignment, and it’s done. It is absolutely done. Now of course I didn’t control the whole getting published part, but really, I just got to work writing stories. And so, by the time the third story was published, I had six stories altogether as the basis for this collection and that’s what we went to market with and my agent managed my expectations, as you know, you’ve probably heard this is a fiction writer yourself that publishers don’t want short story collections. Readers even tell me, “I usually don’t read short stories” or “this is the first short story collection I’ve ever read. I don’t like short stories, but…”

And so, I went into the process with a couple of thoughts. One, I did not have high hopes that this was going to be an easy book to sell. And that if it did sell that there was not going to be any big fat advance or anything like that. And that was fine because I just wanted the book in the world, and I was willing to self-publish it if it didn’t get a deal, like I was cool with that. And so, I felt like I was going into it emotionally in a good place.

The other thought that I had was that, sure, somebody may want to publish it, but based on horror stories, I’d heard about publishing, I just envisioned this editor, a white editor, which is more most likely going to try and whitewash the characters. Because there are no white characters in the book and the gaze is Black woman’s gaze, exclusively.

And there’s a lot of Black culture, Black Southern culture. I don’t translate it, I don’t explain things, I assume a reader who either has the familiarity or who knows how to Google, but I knew from other writers that that kind of approach could be challenged and I was so defensive. It was this process was like, I’ll publish it myself, or if you want to publish it and you want me to change it, I will save this advance and give it back to you if you try to ask me to compromise. You know, I love editing, I love being edited. I love working with like really smart editors, tough editors, insightful editors.

For me, the best part of writing is revision, so it’s not like I didn’t want to revise or I didn’t want to be edited. I wanted that, but not on those terms that would diminish, because, to me, any of those kinds of changes that presume a white audience or center a white audience, would be diminishing my work. And so, I was not going to do that and I was prepared to walk away from anyone who expected me to do that, but lo and behold, no one asked me to do that.

West Virginia University Press, my agent was in touch with the head of the press while I was still working on writing the stories and getting them published, and he shared interest with her at that time. So, when the collection was ready to go out as a partial manuscript, they were definitely on the list. Everyone rejected Church Ladies, except the West Virginia University Press. And I say that proudly because I think it says a lot about the publishing industry.

And I think it’s something to encourage writers who experience a lot of rejection that it’s not personal. It’s not always a statement on the quality of your work, because it’s not like they accepted Church Ladies and then had to massively overhaul it. You know, it’s not so different, a book than the one that so many folks rejected, it’s a matter of fit, it’s a matter of just finding one yes. One entity to say, Yes, we see a vision for this, as you have written it.

Sure, we’re going to edit to tighten it up and make it clear and make it more cohesive and coherent and make it the best work it can be, but the bones of these stories remain the same. And so, it definitely is an underdog story and I hope you know, that people have been encouraged by that.

Dawnie Walton: Well, I think there are so many lessons in that and I am so grateful for so many aspects of that story. First of all, to your agent for having sort of seen the vision, seeing the theme and saying, “I think we can do something with this. Like, if we have three, this is the base.” And I don’t know that I’ve ever heard of, you know, I feel like most fiction – like, we have the completed thing that we’re taking out to editors and it’s amazing that your agent said this is strong enough for us to take out and the right person will say yes. Incredible.

Deesha Philyaw: She knew. And so, something I do now in all my spare time is I poach people away from their agents if their agents are not good to them. I’m like, “Do you want to talk to my agent?” Because this is how—your agent should be skilled enough to help you grow as a writer if they’re like an editorial agent like mine is. But they should definitely be like a fan. They should be like a cheerleader, they should be championing you, they should be encouraging you and challenging you, and really celebrating you, and checking in and saying, what’s next? And what about this?

And what I’m finding is that that’s not always the case. And so, I have a lot of people that reach out and they’re so happy, as all of us are like when an agent finally says yes to us, we feel so thankful, right? We forget that agents work for us and that they should be…

Dawnie Walton: The agent works for you, absolutely.

Deesha Philyaw: Say it. And they have to earn that commission. It doesn’t stop when the book deal is signed like there are other things that your agent can and should be doing for you.

And so, I’ve been just so fortunate to have that kind of agent and so I’m always like whispering and telling people like, “You don’t have to put up with that. Like, really? Your agent doesn’t answer your emails. Are you serious? Are you struggling with your editor? And you cc’ed your agent and they acted like they didn’t see that? Fire them,” you know?

Dawnie Walton: Right, well, I know. So, we have a whole other episode. We’re going to go very deep onto everything about…

Deesha Philyaw: Don’t get me started.

Dawnie Walton: The last thing I want to say is, I’m so grateful to you for sticking by your vision of what you wanted this collection to be because you’ve been talking about this book now for a very long time. And I imagine that it would be a different situation if you weren’t wholly proud of this book.

And I feel like this is a book in which it is just so beautiful, it reminds me of home, it’s so familiar and warm. I recommend it all the time. It is that kind of book that people who don’t read short fiction, it’s they say, like you said, “I don’t normally read short fiction,” but these stories, there’s something in them. And I think that ties into your dedication to what it is that you wanted these stories to be, which are stories for and about Black women. So, thank you for that, Deesha.

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you.

Dawnie Walton: Along the themes. So, of course, all these stories are about church ladies, specifically Black women who are in some way connected to Christianity, even if loosely through their mothers or mother figures. But for me, the third time I read this collection, it occurred to me that I had also kind of like not thought very much about another word that’s part of the title, which is “secret” and these stories are teeming with secrets. And I’m just curious to know the role that secrets play in your fiction when you’re sort of coming up with inspiration for these stories or for any stories that you’re writing, really.

Deesha Philyaw: Sure, so one of the ways that I continue to grow as a writer and one of the challenges I’ve had writing short stories and working on my novel is that I have to remember, I have to kind of work extra hard at coming up with high stakes and to allow conflict and messiness and tragedy to befall my characters because there’s no story without conflicts and messiness and something at stake and the higher the stakes, the better.

And that’s just, I think, kind of basic storytelling. And secrets are just the site of so much potential, potential conflict, potential messiness, having something at stake. The stakes are around keeping something secret, you know, what is at stake if that secret gets out. And so, it’s, I think, asking what your character’s secrets are deepest, darkest secrets, or most delicious secret, or the secret that would change everything if it got out.

And then also with secrets, there’s the elements of surprise, there’s the revelation that comes with—what’s the word I’m looking for? With secrets, that’s the word. There’s the revelation that comes with it. And I was talking to Kiese Laymon about this one that we both love stories where we’re aiming less for resolution and more for revelation.

And so, secrets once revealed, what do they reveal and not just the obvious, which is the secret itself, but what does it reveal about your characters and their circumstances, and their future? Not just the secrets, often things from the past, but what does it mean for the present? What does it mean for the future? So, secrets are just ripe for fiction and imagination because of that core basis of conflict and having something at stake.

Dawnie Walton: I’m so glad you used the word “ripe” because when I think about these stories, I think about how juicy they are. They’re so juicy and like page-turning. And I think as baby writers, before we know how to craft a story, you kind of have this idea, because literature seems very overwhelming. It seems like something very mysterious and whatever you write, it has to be super subtle or super quiet. Do you what I mean?

And I love that this book is just explosive and sort of like it’s resisting that idea of the subtlety, and it really is? I mean, I think secrets and high stakes are key to a good story that has tension and conflict and all of those things that, for some reason, when we’re younger writers, we tend to kind of lean away from that because we think it’s not artful for whatever reason.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, yep.

Dawnie Walton: But what it does is makes your stories like exciting and relatable.

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: So, mothers and mother figures also loom very large in the collection. So, there are ideas about the shame that they pass to us, the examples they set, and the beautiful memories that we have of them, even if the relationships are strained. You mentioned that you hadn’t noticed certain themes emerging in the stories you were writing. Was this one that you were conscious of or intentional about, or was it one that kind of occurred to you later?

Deesha Philyaw: It wasn’t until after I turned in the completed manuscript to the publisher that I was like, “Huh, there’s a lot of mother-daughter stuff in this.” And I know that just sounds so disingenuous because there’s so much mother-daughter stuff, but that’s just how much of that came from my subconscious and I think it was because — not I think, I know it was because my relationship with my mother was the defining relationship of my life.

And, she died of breast cancer when she was 52 and I was in my early 30s. I thought when she passed away, I said everything I needed to say and I think she said everything she wanted to say. And we were as close as we’d ever been in the six weeks that she was in hospice.

And I felt like we both were able to let go and there was no unfinished business. Ha. Clearly, there was a lot of unfinished business for me, and it showed up in my stories. But I think that that’s what can happen when we don’t do that thing you were just talking about, which is like worry about, is this artful? Is this subtle enough? I think if we trust, like, for example, what Toni Morrison said about memory because a lot of my stories are rooted in the memory of my childhood and growing up in our hometown of Jacksonville, Florida.

And so, of course, there are memories of my mother and other Black women and church women, and outside of the church women, Toni Morrison said, “The act of imagination is bound up with memory.” Wow!

That just gets me so excited and I feel like that’s a great way to describe how these stories came about, but they’re bound up together, you know? And that’s how it was for me, that when I start imagining stories and bringing in these feelings of nostalgia and these memories I have and seeing what emerges, if I am not trying to force something, whether it’s a style or a tone or a Message with a capital M.

Something really lovely and necessary emerges, and for me, it was the mother-daughter stuff, because it’s in pretty much every single story in the collection, some dynamic between mothers and daughters. Sometimes there’s a mother who is dying or silent, but still very much present in the narrative and present in her daughter’s life and thoughts, and then there are other mothers that are more present physically and in other ways like Olivia’s mother in “Peach Cobbler.” So, it sort of ran the gamut, but that was a lesson for me in just trusting myself.

Dawnie Walton: And I know we’re going to talk about “Snowfall” later, but that was the story for me where memory sort of almost enters a trance-like state. And when I read that story, I feel the world around me in my home in New York just falls away and I feel this ache in my chest because…Like, I remember there were so many specific memories in there that felt similar to mine in a sense, The Young and the Restless and Grandma, and like the clothespins outside on the line, like all of those things and the way that you structure the sentences. Well, we’re going to get to that, I’m getting ahead of myself. I’m curious, what story in the collection is the first one you wrote?

Deesha Philyaw: “Eula.” “Eula” was first.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, so the first one that appears in the book is the first one you wrote. And then what was the last one you wrote?

Deesha Philyaw: The last one I wrote is “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands,” even though it doesn’t appear last. It’s next to last in the book.

Dawnie Walton: Interesting, so what was the journey for you as a writer between “Eula” and “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands?”

Deesha Philyaw: Oh my gosh. You know, when I was writing “Eula,” I was not at all aware that I was building a collection. Just, that was a standalone story, no expectations of anything at all. It was just this idea that I had around the fact that it’s in traditional evangelical Christianity, especially the more restrictive sects, you know, there’s all this talk about not being tempted. So you’re not supposed to have sex before marriage. You’re not supposed to marry anyway other than heterosexually, and women shouldn’t be alone with men, lest men be tempted, lest they be tempted. So, there’s a lot of restriction and constraining and a lot that’s forbidden and the burden, I know you’ll be surprised, audience, is on women to maintain all of these rules.

And so, as a result, who do women end up spending most of their time with? Other women. And whether we’ve been repressed or not, we’re all, by nature, sexual beings. And we have these desires, what do we do with them? Oh, and by the way, masturbation is forbidden too, right? So, talk about a perfect storm, right? So, you’ve got all these hormones and you’ve got all these restrictions and the propensity to hide things, because the idea is the church is the original don’t-ask-don’t-tell institution, right?

And so, as long as you don’t flaunt things, as long as you don’t get caught at things, right? So, I was like, this is so right that we’ll never know how many church women have sex with each other because it’s an outlet. You agree to keep each other’s secret, right? Because there’s a mutual benefit to keeping that secret and no one’s the wiser. And I was also thinking about sort of the ways that brand of Christianity can really infantilize us as adults and really kind of oversimplify life with this sort of really weird rule system, right?

So, you can do whatever as long as you ask for forgiveness but if God is really in your heart, you won’t want to do those sinful things anyway, right? And it’s like, wait a minute, slow down. I can’t keep up with that. That was me as a kid, I was thoroughly confused by all of this, but I thought about how that manifests for different people. So, I knew of this couple in college that the guy in the couple became Christian in the midst of their dating. And so, they would pray for forgiveness first, then have sex, and then pray for forgiveness afterwards.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, oh no.

Deesha Philyaw: So, in the church that’s called following the letter of the law, but not the spirit of the law. So, I was thinking about that, I was thinking about how women, especially older women who haven’t gotten married might handle this. And that’s when I got the idea of these two women who get their needs met with each other, but they have their code, which is, we’re only going to do this once a year. And then in Eula’s case, she’s going to pray about it, that’s for forgiveness.

Dawnie Walton: In the shower with the shower cap on.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly. And then reset until the next time. And, of course, who doesn’t love a good “Same Time Next Year” kind of story? You know?

Dawnie Walton: Oh, amazing. So, we’ve talked before about how the first story in a collection sort of sets the table for the entire collection in terms of giving the reader a taste of what’s to come and letting them decide, are you going to rock with this or not?

And I think “Eula” serve that purpose. It’s one of the stories that kind of lays out these ideas about the hypocrisies of the church and quirks of the church. And I’m curious, so for the real-life church ladies, who’ve read this book because I know there have been some. There have been some Book Clubs and all that.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh, yeah.

Dawnie Walton: Is this the story that you get the most scandalized feedback about? Or how does that work?

Deesha Philyaw: So, the people whom I hear from directly, they’re not typically scandalized. They are excited, like “What?! Okay, I’m in,” you know, strap in, let’s go. But what I’ve heard from more than one person, which I think is hilarious that multiple people have been doing this, is they will send this book to like their mother or their churchiest auntie and with no explanation, none.

Dawnie Walton: Huh?

Deesha Philyaw: So, the first thing they would read is “Eula,” and so then will text or call the person that gave them the book, usually another Black woman, and be like, “What is this?”

Dawnie Walton: “What you got me reading?”

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly! But they keep reading,

Dawnie Walton: Of course they do.

Deesha Philyaw: Which is, you know, that’s the thing. I mean, I’m sure there are some people who pick this book up, read “Eula” or started reading “Eula” and were like, “No, hell no.” But like mine, I have three aunts, and when I did an event with the Jacksonville Public Library like you did, they all came out and they got copies of the book and, we were in the parking lot and I said, “Listen, you guys are going to get home or at some point, you’re going to read that first story, do not call or text me. Text and call each other.” Just, I tried to warn them the way others have not. I think it should come for—if you give this book to a church lady, there should be a warning before they read “Eula.”

Dawnie Walton: Well, it’s all kind of meta, right? Because their secret is that they’re reading this very juicy book.

Deesha Philyaw: And I won’t name the aunt, but while we were at the event, I whispered to one of my aunts, because she used to bring home from her job because she worked at Duval Publishing Company and those books that they can’t sell anymore, they take the cover off or whatever, and there were some like racy, sexy books in there that I would sneak and read. I would go into her closet and when I was at my grandparents’ house and read it and she was horrified.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, yeah. I mean, those ladies, they have Zane, they have like all of them books.

Deesha Philyaw: And this was pre Zane, this was the ‘70s and ‘80s because I’m old. And so she was like, “D!” and I said, “Don’t worry. I’m not going to tell anybody.”

Dawnie Walton: I love it. So, it’s interesting this time when I read this story because this is the third or fourth time I’ve read “Eula.” The thing that struck me this time is the setting that you choose. In terms of the themes of the story are very timeless, but it occurred to me, “Oh, this was very intentionally set on New Year’s Eve 1999, heading into 2000.”

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: And I was curious why? Why that year?

Deesha Philyaw: I think it’s, if memory serves, because it’s been a long time, I think I took a workshop on, I want to say it was David Haynes’s workshop on the narrative engine. I am a Kimbilio fellow and David founded the Kimbilio Center for African-American Fiction, and it’s a retreat and a fellowship just for Black fiction writers. And his craft talk that summer, when we were in Taos, was about the narrative engine and he introduced this idea of having a clock ticking, literally or figuratively.

And so, I was like, “That’s what this story needs. It needs a clock ticking.” And I thought that Y2K was a fun clock and Y2K came and went and we just sort of moved on with our lives. So, I thought it would be fun to kind of go back to that moment when we didn’t know what was going to happen.

Dawnie Walton: Right, so much uncertainty, so much tension and then you combine that with the countdown that happens at the end, it’s sort of like it’s a climax in more ways than one, let’s just say.

Deesha Philyaw: It is, exactly. And you know, what was fun about that ending and that climax, Denne Norris, who is now the editor-in-chief of Electric Literature at the time, was the fiction editor at Apogee Journal, which published “Eula” before the book came out. And so, Denne was doing notes and revising and we were literally, the day they were going to publish, because it was in print, it only recently is available digitally on the website, but they were about to go to print and Denne was like, “Can we just go through these notes? You know, just a couple more things.” And I just dropped everything and was like, yes.

And we were in the Google Doc together and like, the ending just wasn’t working and with Denne right there, like watching me type and then backspace, backspace, type, like, and it’s weird. It’s like having somebody read over your shoulders when you’re writing. I never have that. And then that countdown just came to me and Denne was like, “Yes!” And then we sent it out into the world.

Dawnie Walton: That’s amazing.

Deesha Philyaw: So, talk about writing under pressure, right?

Dawnie Walton: The pressure of the ticking clock.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes! Literally, I was writing a ticking clock as the clock was ticking, yes.

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: The other effect that the countdown had for me, was it had me sort of thinking about the characters past the ending. And I wonder if you also think about your characters past the ending and what you imagine happens with Eula and Caroletta after that countdown or do you know?

Deesha Philyaw: Sure. So typically, I don’t think about them afterwards, but there are two exceptions. One, because of my HBO Max show, I’m thinking about them now after what happens next, we’re moving forward in time. The show is actually going to be set in the present.

And so, a lot of the script that I’m writing is where are they now basically? And what’s happening? And what has happened since we last saw them in the book? But the one character that stayed with me after I wrote their story was Olivia from “Peach Cobbler.” But again, subconsciously, I didn’t know that she was still with me until I was writing “Instructions,” which is the last story in the collection and I got…

Dawnie Walton: …You’re about to confirm a theory of mine. Yes, yes. Go on.

Deesha Philyaw: So, there’s a section in “Instructions” early on where she’s sort of talking, the narrator, whom we don’t know who she is. And I didn’t know who she was as I was writing to her, I was writing to discover her, and she says something like, “I own a bakery and I make the best peach cobbler in town.” And I wrote that line and I was like, “It’s Olivia!” and I surprised myself and I used to roll my eyes when writers said that their character just showed up and told them who they were, I’m like, “Yeah, right.” No, that really happened.

And I think it was because while I was happy with the ending of “Peach Cobbler” where Olivia is sort of stuck with the mother she has because she doesn’t have anywhere else to live, my heart, like, Olivia just stayed with me, like, that poor girl. She’s so many of us who were stuck, like, our homes are places that we have to suffer through until we can get out, you know?

I mean, and my home was not, you know, let me not be dramatic. It was not as bad as it was for Olivia or anything like that. But I think that that’s the reality for too many of us; we are pretty much at the mercy of the people who raise us because if nothing else, we just can’t afford rent, you know? And so, she stuck with me for that reason I think, because it’s like, well, what ultimately happens? Where does she land? And given who raised her, whom does she become? And is she happy? Is she free? How has she, relative to her mother, what kind of choices is she making now?

And so, she pops up in this story. And I think once again, I don’t know that I resolved anything. There’s no real resolution because the interpretation of that revelation of where she lands is, we see Olivia as an adult through our own experiences, our values, our fears, and our desires. And so, there’s no one answer, but I love asking Book Club people when they invite me to talk, they’re asking me questions, I love to ask them the question, “Is Olivia happy? Is she freer than her mother?” And people are able to do something that, you know, we are not always good at with this kind of nuance, which is to say, “I wouldn’t do what adult Olivia is doing,” which is serially sleeping with married men, but I’m happy for her, right? I mean, that’s what you want, right?

Dawnie Walton: Listen, the voice of that story. So, let’s skip ahead to that story. So, the voice of that story is so strong and so declarative and so sure that you can’t help, but kind of be a little bit like, “Okay, Miss…” like a little bit, she is very much in control.

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: Very much like this is what it is and is very self-aware of what brings her pleasure and not very judgmental of herself for that.

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: And I had to kind of admire her a little bit, even though you do kind of go into that story, like what kind of person is this?

Deesha Philyaw: Right, right.

Dawnie Walton: And so, the added knowledge of that sort of “Peach Cobbler” could become a kind of like a backstory for this character.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: And so, it has kind of an interesting effect there, but I would say that she is… Is “happy” the word? Satisfied, I guess, would be the word for me. What do you feel about Olivia in that story?

Deesha Philyaw: I think, especially knowing her background, I’m happy for her. I think happiness is fleeting though, you know?

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

Deesha Philyaw: And we define it differently and I think that by her own definition, she is happy because for her being in control is the goal. And so, she has succeeded because ultimately, she controls these relationships. Now over time, she may find that she doesn’t get the same satisfaction. And that’s why I anticipate that this is not really sustainable.

Dawnie Walton: Right, this detachment, this never getting involved or emotionally or anything like that, yeah. But one thing you know for sure is that she will never be sort of beholden to a Pastor Neely.

Deesha Philyaw: Right, right

Dawnie Walton: You know that.

Deesha Philyaw: Well, and here’s the other thing too, not only beholden to a man like that, but she will never be at the mercy of anyone the way she was at her mother’s mercy. And I think that’s just as important for her.

Dawnie Walton: One thing that I also, kind of changing gears a bit, that I picked up on in this read, “Eula” also to me kind of tweaked some of the pop psychology around how to get and keep a man, like I’m thinking about all this stuff that men put out like Steve Harvey, Think Like a Man and all that, which it’s very, for lack of a better word, it’s a problem, I feel like a lot of times. Was that something that was on your mind when you were writing this story or am I just reading into that?

Deesha Philyaw: No, it definitely was, but not Steve Harvey specifically, though Steve Harvey was like a few years after—or maybe, you know what, there was probably some overlap in the, like the late nineties.

Dawnie Walton: All that stuff around The Rules. Like, there’s always been versions of it. It’s not just like Black folks too. It’s been like all kinds of crazy stuff coming from men about what women need to do.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly. And it was during that era, the thing that stood out to me was this “Waiting for my Boaz.” And I think it’s such a misreading of the Bible story because she doesn’t…It’s not like she was dating, Ruth in the Bible. It’s not like she was going through a lot of dudes and then it was like her Boaz showed up or like men were trying to date her. And she was like, “No, no, no, I’m waiting.” It was like her mother-in-law, her husband had died, and she was a widow. Her mother-in-law is like, “Hey, there’s that guy over there, go lay down with him,” you know?

So, there was no waiting, and he was good, he kept them from starving. So, yes, he was a good man. But somehow, Christians in their infinite mediocrity, got hold of that story and it turned into like a whole cottage industry, because all it was designed for was to try and tell single women don’t have sex, that’s all, before you marry. You’re going to wait for your Boaz. You’re waiting for the man that God has for you, basically.

Dawnie Walton: And yeah, and it becomes this whole other kind of dogma in religion.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly, exactly. And so, I mean, they did, it was like the mugs and the T-shirts and the whole thing, because, of course, we have to commodify these things, right? Christianity. What is the Twitter thing? It’s like Christianity and capitalism shaking hands? And it was like between the waiting for the Boaz and the Proverbs 31 woman, that was also that moment the godly wife and it’s a set of verses in the book of Proverbs that describe this godly wife who is just impeccable in every way and a servant. She doesn’t sleep, she makes her own cloth, it’s like basically, we’re supposed to do everything. And so, that is also the standard and that was also commodified in the nineties and the early 2000s.

So, I was thinking about that, but to your point, it’s a long tradition of these templates for who we should be, always driven by men and even Steve Harvey and some of the other incarnations of it seem to be secular, but they’re all rooted in Christianity, in Christian dogma.

Dawnie Walton: And patriarchy…

Deesha Philyaw: And patriarchy,

Dawnie Walton: …All that, yep, yep.

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: You know, I can talk about you all day, but moving on to “Not Daniel,” story number two in the collection, and this is a story, this is probably one of the shorter, this is the shortest story in the collection, I believe.

Deesha Philyaw: It is.

Dawnie Walton: And that the narrator is connecting with the man that she meets at a hospice center while both of their mothers are dying of cancer. And so, although it’s so short, it’s touching on so many big things: grief, guilt, pleasure, comfort, and so much more. And this, Deesha, is where I struggle as a short story writer because I don’t know when to shut up.

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: And when to stop following all the threads that I’ve put in the piece and let a single moment or a single encounter carry that weight. So, how do you know where to begin and end your stories and especially like this story?

Deesha Philyaw: I can relate to that. The first writing class I ever took, because I don’t have an MFA or any writing-related degrees, and my first writing class was at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts and it was a flash fiction class, and I just was not successful in that class at all because I could not write flash to save my life, I just couldn’t do it.

The teacher was great, and my classmates were wonderful. We read great flash pieces, I was so inspired and I just couldn’t do it. And what I discovered, and it’s not like I was aware of it at the time, but looking back, and I think this is true for so many of us with our writing, whatever we are going through just as people, it’s going to influence the writing. And I know that sounds like, duh, but this is what I mean. I was at a place where there were so many things, especially rooted around my relationship with my father and also in my first marriage, where I felt unheard and I felt misunderstood and I felt ignored. And that showed up in my stories because I felt like I had to explain everything.

And so, I was committing what this one craft book called “had horrors,” which is, you talk about what had happened and you stopped the present action cold. And to this day, when my agent is reading my work to edit it, she’s like, “Okay, make sure we get back to the present action quickly,” because I will digress. And so, what has helped other than getting past the fact of feeling like I have to explain myself in my personal life and healing the wounds that I had from childhood around being misunderstood or dismissed or ignored, healing that helped me to be a better writer because then I felt less compelled to explain things and I could trust myself more and I could trust the reader more, that in these smaller strokes in well-chosen turn of phrase, a small description, it could speak volumes.

I had to get healthier emotionally. I had to grow in skill as a writer to learn how to do that before I could write a story like “Not Daniel” and then having a ticking clock again at the outset can help as well. And so, I knew going into that story that I wanted the story to span the length of one sexual encounter. And so, yes, there are some places where I have some flashbacks to some earlier scenes, but the beginning was going to be the start of that sexual encounter and the end was going to be the end of that sexual encounter. So, it’s like, when you go bowling and you don’t know how to bowl well, like me, you put those bumper things in. It’s like that. You know, it’s like build it in.

Build into those parameters, set that clock to ticking, like, this is the space we have. And being conscious that when I did those flashbacks, they’re very brief, which means they’ve got to be the most impactful things that I can think of, and so that’s how that one came about. And then endings in general, I like to end on what I call a “sigh,” which can be interpreted in a lot of ways. It can be like, we’ve talked about an earlier revelation like something’s revealed, resignation, you’re resigned to something, celebration, or just sort of bliss, like think of all the context in which we sigh, and I like to end on that kind of note in a story.

Dawnie Walton: I love that going into the story, sort of knowing the tone that you want, the ending to be because I often don’t know. I’m not a planner. I don’t outline very much, I don’t know the specific details but what I do know is the feeling that I want to have at the end.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, yes. And trust that, because I think so many of us have been told, just like you were talking earlier, like, oh, these rules that are really just elitist and gatekeeping rules, like it has to be subtle and it can’t be sentimental and it has to be ambiguous. And the ending has to have all of you, you’ve got to outline and all that stuff, you don’t have to. But to say, I mean, that’s such a profound thing you just said, “I’m going to go with the feeling.”

And those are the best stories, right? Where you can tell that the writer wasn’t worried about all of that other crap but they were feeling something. Now we are feeling something, it may not even be the same something, but ultimately that emotional connection with the story, with the characters between, and the story is the conduit of connection between the author and the reader that we can trust that part of us that’s tender. We can trust that part that simply feels, and that’s valuable.

You know, when we try to say that it always has… Well, first of all, it’s a false dichotomy between the rational mind and the crafting mind, if we could call it that, and the emotions. I think emotion and craft in writing, they’re just inextricably tied. One is not superior to the other. And I think we’ve elevated this idea of craft at the expense of the emotional part. And then for those of us who have marginalized identity, it’s assumed that somehow, we don’t think about craft at all, you know? And it’s not, it’s that these things are working in tandem. And I think that people are more… More writers are capable of doing that. They just don’t give themselves permission to do it.

Dawnie Walton: Well, you’re segueing beautifully to “Dear Sister,” which for me in the collection was a really beautiful illustration of complex emotion with craft and the way that you combine, or juxtapose laugh-out-loud, funny moments also with painful moments.

And there’s a little section that I want to read really briefly if you don’t mind, in which the narrator’s Uncle Bird, is reminiscing about a conversation he once had with the narrator’s late father, Stet. So, Stet…

Deesha Philyaw: I’m laughing already.

Dawnie Walton: Stet, listen, listen, listen, Stet done had a lot of babies all around town. And in this story, Nichelle, on the occasion of this philandering daddy’s death is writing a letter on behalf of her adult sisters, to another sister they’ve never met. And so, she’s talking about her Uncle Bird, and he says of her father, he says once to her father, “’You the only motherfucker I know describe his kids like a Spades hand.’ Uncle Bird mimicked my father’s slow drawl. ‘Uhhh… I got five and a possible.’ We both laughed. And then Uncle Bert was crying again. Grief is like that. He hadn’t just lost Stet. He’d also lost his four other siblings, all too soon. To drugs violence, or both. We barely got to know our aunts and uncles.” And so, like how you go from a moment that is so hilarious, right? But also, deeply painful because it’s a funny memory, but it’s also like Uncle Bird really misses Stet. It’s his last living sibling, you know?

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: And it’s just like, so, so touching. And this story, okay, this story had…this story was so Black. I was like, wow. It had the pet names, it had the Spades reference. It had dreams about fish, right?

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Which is like a folk thing down south with us Black folks. It has Tasheta punctuating quotes, each word of her last sentence with a clap. And my favorite part, right, about the pastor at the funeral, “And then he did the thing pastors always do at the funeral of someone who hadn’t darkened the church’s door in a few decades: reminded mourners of their own mortality and where they are likely to spend eternity if they don’t get right with Jesus.” Listen, pretty much every funeral I’ve been to this is like that.

Deesha Philyaw: Wrap it up, shit, wrap it up!

Dawnie Walton: So, one of the things that bring me the most joy about like reading, and writing, that I really love is I imagine the writer and the process of them writing. And I imagine them sort of laughing to themselves as they’re writing the story. And so, I’m picturing you sort of writing the story, but like tell me what it was like for you to kind of go through all of the spectrum of emotions?

Deesha Philyaw: Sure.

Dawnie Walton: And to create these characters, because there’s a lot of characters in this story it’s very heavily populated and yet each of the sisters is very distinct and memorable. Anything you can say about that?

Deesha Philyaw: Sure. So, “Dear Sister” is the most autobiographical story in the collection, because my father too was a rolling stone and I have four half-sisters, I’m sorry. Yeah, four half-sisters that I know of. We always said “that we know of,” and the four of us, we didn’t grow up together, so that’s different. And that’s one of the things I wanted to create in the story is to give those sisters relationships with each other that I didn’t have with my sisters, unfortunately, and as messy as they are, they’re still very loving and they’re very close.

And so, one of my sisters, our mothers kind of raised us close, but the other two, we knew each other and we met a few times, but we did not really connect until the occasion of our father’s death. And so, we were sitting around my stepmother’s house the week of his funeral, I was down in Jacksonville. And just as an aside, I remember that was when Superhead’s book came out.

So, we were actually sitting around the dining room table, reading parts of that book out loud and scandalizing our stepmother’s mother who said to us, “You know, you guys have another sister, don’t you think she deserves to know that he died? You should be in touch with her.”

And so, we were like, yeah, we should. We knew of her and we knew that like, she didn’t want anything to do with our side of the family, understandably. And so, it’s just such a random thing. Our stepsister had her phone number, long story, won’t get into that. And so, we were like, “Let’s call her.” Yeah. All four of us were on speakerphone.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, wow.

Deesha Philyaw: And can you imagine getting that phone call, right? That’s too much because one, it’s just overwhelming and it’s emotional for someone who… You know, this was not a chapter of her life that she wanted anything to do with, and then for the four of us to call at once, implied that we were this collective and that we had had something great and she was on the outside of it, and that nothing could have been further from the truth.

And so, needless to say, she was not like—she was polite, but she wasn’t. We were like trying to meet up with her and she was like, “Okay.” Yeah, and then that didn’t happen for years. 2019 was the first time we were all together and we called her in 2005.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, goodness. Wow!

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah. So, “Dear Sister” is an epistolary story, so that should have been a letter, you know?

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: That was the right way to do it. So, it was a do-over in that. I could write how I wish we had handled that; I could write what I wish my relationships with my sisters were when we were growing up. And it’s a little bit of a revenge fantasy because the moment at the graveside where the father’s daughter, one of his friends hits on her, that really happened, that really happened and I was too stunned to do anything. So, I just stood there and then I just walked away. And then later, I was like, “Why didn’t I cuss this man out?! Why didn’t I do something?!” And so, I got to do it in the story.

Dawnie Walton: Right. Well, I love that as inspiration for stories, because my novel was basically wish fulfilment, like wishing that Opal Jewel existed and like that’s one of the most fun things about fiction, it’s creating the world that you wish had been.

Deesha Philyaw: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: And living through the story in that way.

Deesha Philyaw: And you know what, you asked me about the side-by-side emotions of sadness and laughter and that’s a gift that my mother gave me before she passed. Those six weeks in hospice, we laughed more than we cried.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, that’s beautiful.

Deesha Philyaw: And I always joke that like around that same time I was getting divorced. And so, between my mother dying, and getting divorced, like I developed a sense of humor and maybe it was like a survival mechanism, but I think I had been a very humorless person up until that point. I was a very, very serious person. But my mother just sorts of modeled that for me. Like she was just unabashed and just funny and blunt and you know, because I mean you’re dying, right? So, why not say whatever the hell you want?

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: What can people do? Do you know?

Dawnie Walton: Right, right.

Deesha Philyaw: So, it’s just like a gift that she gave me and it just showed up in my writing. But especially in “Dear Sister” and you know, Tasheta in that character in particular.

Dawnie Walton: Yes.

Deesha Philyaw: I remember writing some of the foul stuff she says, and I’m like, “No editor is ever going to publish this. I just know they’re going to make me take it out, but I’m going to put it in, I’m not going to censor myself,” and they didn’t take… And my editor, West Virginia University Press like we’ve talked about it. She was like, “Oh no, I never thought about taking it out. I love Tasheta.”

Dawnie Walton: It’s amazing, she’s great. And as a reader, like you said, like she’s so pleasurable to read because she just does and says anything and on one hand, it’s like, Ooh girl, what are you doing? And then, on the other hand, it’s just hilarious.

Deesha Philyaw: Right, I’ve had guys DM me like, “I want to meet Tasheta.” Sir, she’s not real.

Dawnie Walton: It’s a compliment to you though, as her creator, right?

Deesha Philyaw: How are you going to slide into the DMs of the author? You know, the fictional character’s creator, I want to holler at her.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, I love that story so much.

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you.

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: And then, so now I want to talk about the first lines. Because the next story of course has I think what is going to be one of the classic first lines of short fiction. “My mother’s peach cobbler was so good it made God himself cheat on his wife.” When and how did that line come to be? Was it always the first line of this story or did it emerge later?

Deesha Philyaw: No, it was the first line. I got the idea for this story because I wanted to submit it for consideration for this food-themed anthology. And I just remember thinking, I wanted to write about a dessert and I was like, what’s the Blackest dessert I could think of? And I thought about peach cobbler, which, scientifically, I can prove it’s not the Blackest dessert, pound cake is the Blackest dessert.

Dawnie Walton: I was going to say pound cake or sweet potato pie has a good claim.

Deesha Philyaw: But for whatever reason, peach cobbler came to my mind. But it’s so much better than either pound cake or sweet potato pie because of the textures and the sweetness and there’s a sensuality to it that the other two don’t have.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

Deesha Philyaw: But I was thinking of the Blackest dessert and whatever that came to mind. And then I was also thinking about a story that I had written many years ago as a baby-baby-baby writer, and it was based on my childhood experiences of who I thought God was. It was so literal, as kids are, that when people said God was up in heaven, I thought God was in the cloud, so I would literally like look at cloud formations and try and find God’s face and like the beard because I think I was confusing God, and Noah, and Moses, you know, all these pictures. So I thought that literally, and then I also got confused about God and pastors of churches, because they would be reading the Bible or speaking in, the voice of God and saying “I,” and I thought that the men standing in the pulpit were God.

But then my mom took me to this revival once when I was like five, no, yeah, maybe five or six. I was young. And suddenly, there was a woman-pastor and she was absolutely beautiful.

Dawnie Walton: Wow.

Deesha Philyaw: And she had on this white clergy robe and I didn’t know what to do with that because she was in the role of God. But even though they did that, there’s the whole verse about God being, you know man and woman, he made both in his image, which is kind of contradictory, but my 5-year-old brain couldn’t handle all of that.

And so, I wanted a character who was little, like I had been, trying to grapple with this notion of “Who is God” and thinking that the pastor was God and then, sex on the brain, it was like, “And he’s sleeping with her mother. Go!”

Dawnie Walton: That’s amazing.

Deesha Philyaw: And then you bring in the peach cobbler and I had my blueprint, I guess.

Dawnie Walton: So fantastic. So, it’s such a heartbreaking story and it’s about a narrator who is really just starved for her mother’s love and the mother was probably, for me, the most challenging character in this collection. I felt so angry with her, so frustrated by the coldness and cruelty toward her daughter and then sort of what she’s setting up inside her daughter, as we see payoff later in “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands.”

How did you feel toward the mother writing to her? Because it’s not as if—I don’t hate her. I do feel some level of empathy for her, but how did you — Were you able to hold some empathy for her and where was that empathy for you?

Deesha Philyaw: So, I definitely didn’t want her to be demonized, but I also didn’t want to tell her backstory because this isn’t her story. It is Olivia’s story, and I wanted to see her through Olivia’s eyes. And so, for most of us, our parents are a mystery. We don’t know sometimes ever why they do the things they do. Or if we do know, we don’t find out until much later.

And so, I knew that Olivia would experience her both through this frustration and this hurt, but also love, you know? And so, Olivia as her child could hold all of these different feelings towards her, and I also wanted to be able to try and convey that to some extent in the story as well. And so, it shows up when she tries to warn her, “Don’t be anything like me.” It shows up when she tells her, “Hey, I’ve done what I’ve done because I’m trying to keep the lights on.” So, it doesn’t make it right.

And it’s not a full explanation or an excuse for her behavior, but I was hoping that it would humanize her. And I think that subconsciously where it came from was the fact that, I’m a mother as well. And I hope that my daughters can see the mistakes I’ve made through some kind of lens of grace, as I’ve had to do with my mother, even though she’s gone. We don’t really see our parents, especially our mothers, as people until later in life, if we ever do.

And so, I think that the reader, our inclination is to see her as a person, as a mother who has hurt her child, but we’re not thinking, she was probably hurt too as a child and it doesn’t excuse it, but can we show some grace and is our judgment swifter for mothers than fathers? Is it swifter for Black mothers? I wanted us to sit with some of those questions as well. Do we have space for Black women to be imperfect mothers? I hope so. Because I’m an imperfect mother.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah, yeah.

Deesha Philyaw: I might not do the things that mother did, but there are other ways where I have not been the person that my daughters needed me to be.

Dawnie Walton: And it’s interesting that the other thing about “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands”, where we see the adult Olivia think about is, do you think she’s reached that space of being able to have grace for her mother for being imperfect? Has she grown in that way to have?

Deesha Philyaw: You know, in “Instructions” when I was writing it, she just sort of eludes to her mother and says, “I said I wasn’t going to be like her,” but here I am doing the same old thing and then I didn’t really think too much about her mother beyond that, but writing the TV show, we see Olivia still engaged with her mother. So, it’s not a thing where she has cut her off. She’s very much involved in Olivia’s adult life.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, wow!

Deesha Philyaw: And so, that’s been really interesting to write and so that relationship is one that we really are excited about exploring on the show.

Dawnie Walton: So, next comes the two stories that I’m very excited to see. I call this the kind of like the couplet of the collection, the romantic section of the collection, the soft place to land, “Snowfall” and “How to Make Love to a Physicist.”

“Snowfall” is, I’ve told you before, it’s my favorite story, for the way that it unlocked memories through those “I miss” lines and the trance-like nature of them, but also just the sort of beautiful act of service that the girlfriend character does for the narrator at the end, which I just like, I would’ve dissolved into a puddle of tears…

Deesha Philyaw: Right?

Dawnie Walton: …If that happened to me in real life and sort of redefining what home means for that character. I don’t even know if I have a question to ask about this story rather than just talking about like what it was like to write it, what your intention was in writing it and how you got into that space of memory and longing that’s in the piece.

Deesha Philyaw: Sure. So you know, the way I connected with “Snowfall” was around that cold and displacement, the physical environment, the first line of that story is “Black women weren’t meant to shovel snow.” And it was a record freezing weekend when I was writing this story. The first draft of it. And was just sort of dreading how cold it was. And I tend to stay in during the winter, and then having to tend to snow, you know, getting somebody to shovel me out or having to do it myself or whatever, it just literally makes me miserable.

And so, that’s how I was sort of connecting with these characters first around this sort of the sense of being from a place where this was not what I was used to. And even after this fall or this summer, it will be 25 years that I’ve been in Pittsburgh and it’s gotten harder and not easier over time. I resent it more as time goes on.

And so, that was sort of my entry point for the story is that I kind of gave my disenchantment and my frustration and my resentment to these characters who have also come from a cold place. And so, the cold is literally a barrier for them, but then metaphorically, it is the opposite of what they’ve known as home and then it sort of turns the question on them, which is, “Where is home now? Are we making a home for each other? And how can we do that when we each have these very different relationships to the homes we left behind?”

And so, that was the impetus for that story and then the main character, Arletha has this moment where she is estranged from her mother, but then she has a literal fall on the snow and ice and her immediate thought, which is primal for so many of us when we are in a wounded place, is I want my mother.

And that’s something that my mother has been gone 17 years and whenever I am in a wounded place, gosh, I want my mom, even though our relationship was complicated, even though when she was alive, I did not often turn to her for various reasons, but now, oh my gosh, it is so primal.

And so, I imagined what that would be, and there’s that complication and messiness of, yes, my heart of hearts cries out for my mother, but my mother has also hurt me and has rejected me and I still want her. And that sort of harkens back to Olivia and her mother, like children cling. Children will keep showing up for us as adults, long after we deserve it sometimes and there’s that piece of it too. So, those relationships are so complicated, and so for me as a writer, just ripe to explore through imagination.

Dawnie Walton: That image of Arletha’s mother in the flashback, sort of pulling her daughter onto her lap with relief. Well, there is a whole like an ice storm. Was it an ice storm or snowstorm that happened in Jacksonville back in the day?

Deesha Philyaw: 1989.

Dawnie Walton: Yes, yes.

Deesha Philyaw: Do you remember?

Dawnie Walton: So, my father worked across the Mathews Bridge and got stuck across the Mathews Bridge for a couple of days because of that storm, but it was a big deal in our hometown. And just that memory that I had along with that sort of really beautiful tender image of mother love because there really is nothing like that mother love that would pull a big old teenager onto her lap, into her arms, so beautiful.

And so, “How to Make Love to a Physicist,” I have taught this one a few times now…

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you.

Dawnie Walton: …For characterization. It’s part of my characterization lesson and the reason I teach it is because it is so wonderful as the reader to see all these sensory details about Eric, that Lyra is sort of like, she has like a little checklist in her head, right? and there are all these things, these little details that are drawing a picture of who Eric might be, and you as a reader, get excited that maybe Eric is someone that she can get excited about.

Deesha Philyaw: Right.

Dawnie Walton: And so, in drawing Eric as a desirable, romantic prospect, right? What were the most important ingredients for him in your mind?

Deesha Philyaw: His intellect and his patience, because without his patience there would be no story because she was trying.

Dawnie Walton: She was… Listen, I mean she ghosted…

Deesha Philyaw: Twice.

Dawnie Walton: Girl, what are you doing?

Deesha Philyaw: A good Black man too.

Dawnie Walton: A good Black man. Listen, he is great, he is fantastic. And so, is Tony from “When Eddie Levert Comes”…

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Whom we’ll talk about in a minute, but the detail that I love the best and I always kind of point an arrow toward in my lesson is when he removes his cap, she sees those moisturized baby dreads. The key word being moisturized. Like, here is a man who takes care of himself.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly. And for me, that is his attention to detail and it kind of spoke to some of my own experiences that if people are careless with themselves, they’re going to be careless with you too, and so in the African-American community moisturization is a key element of caring and good grooming and speaks well. I mean, one of our worst compliments is for somebody being ashy and certainly your locs should not be dull and dry. And so, that was a signal that he is someone who minds the details, and that’s someone who she deserves, somebody that would really see her and really tune into who she is and as great as he is, though, the healing work that she needed to do, she needed to do that primarily for herself. I did not want him to rescue her. That was really important to me narratively, that she be her own savior.

Dawnie Walton: Love that. And let me also ask you, are you involved in the casting of the Physicist for the HBO Max?

Deesha Philyaw: I will be. So, Tessa and I are both executive producers. And so, as such… like we had a dream cast list that we started, as soon as this deal was done. I do have a shared document with Tessa Thompson, very excited to say, and so I’m useless, though, because I will list like every Black person in Hollywood, but I’ve been trying to kind of shape it by character or whatnot. and I’ve been hesitant to say anything publicly about like who I might think, but I’m happy to hear whom you might think would be a good physicist…

Dawnie Walton: You know. Well, listen, I have some inside information about who might be good for the physicist and I am not going to share that right now.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh.

Dawnie Walton: But maybe we will start our own Google Doc about that.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes, I am so down for that.

Dawnie Walton: Yes.

Deesha Philyaw: I am so down for that. Because I do have a lot of Black women listed. I have fewer Black men, so please, please would you like to consult? I need, you know, Dawnie Walton consulted on the casting.

Dawnie Walton: Happy to, happy to, and then we move into “Jael,” which I…

Deesha Philyaw: That’s my girl.

Dawnie Walton: Listen, Jael is… I love her. She’s only 14 and she is incredible. Yeah, but I want to talk for a little bit about her grandmother,

Deesha Philyaw: Granny.

Dawnie Walton: Who is a character who, for me, might be one of the most shocking characters in the entire confession, in the entire collection. I said, confession because I was thinking about the confession that she makes on page 140. So, this is the first time that we kind of get into the first-person point of view with the kind of church lady that the other stories are critiquing in a way. And what was that like for you to kind of inhabit so directly a character like that?

Deesha Philyaw: It just felt like home. I mean, I was raised by my own grandmother; it was my mother and my grandmother there in the house and then for a brief period when I was away at college and when I would come home on breaks, my great-grandmother lived with us. And so, I’ve always been surrounded by older women.

And so, she was the perfect juxtaposition against this 14-year-old girl who is just flouting all the rules, she’s talking about sucking dicks and being saved. And she’s lusting after the preacher’s wife, but she’s putting it all down in her journal, which should be her private place. And then to have her great-grandmother be the person who sees these private thoughts and then tries to figure out what she needs to do about them. It sort of sets them up as polar opposites, but over time we realized that granny isn’t exactly as she presents herself to be. And, in fact, like all of us, she has a past and she has a history. It’s again, how do we choose to frame it?

And she just mentions it very casually the time that she has… I don’t even…No, I think she does say, “God, forgive me.” You know, she recognizes that what she did was considered a sin, but she didn’t dwell on it, you know? And I think that so many church ladies, to use the colloquialism, “contain multitudes,” as Walt Whitman would say, but doesn’t everybody and why wouldn’t they, you know? But I think sometimes we forget because there’s a face that they want the world to see that is pious. I never know how to say that word pious, but there’s always more beneath the surface.

So, whether it’s granny’s secret, whether it’s the grandmothers and aunties in “Snowfall,” the one with the one gold tooth, who’s my grandmother, by the way, my grandmother had a gold tooth. And so, they are just like, even they just embody that. So, my grandmother’s walking around like a grandmother and then she has this gold tooth. So, what was that about? And I never asked her, gosh, I regret not asking her.

And so, in these stories, that’s one of the things I get to do is just imagine who they were. And then how did they get from there to here? And is it that they have a single face that they want to show us or do we only allow them to show one face? Because, I don’t think my grandmother was trying to hide anything from me and she was not a church lady, but I could only see that one dimension of her

Dawnie Walton: And the story of Jael. So, another thing that makes the story unique is that it’s sort of directly drawing from a biblical story or verse. And I have to say, this is a blind spot for me. We went to Bethel Baptist for like three weeks, sometimes late in the late ‘80s.

Deesha Philyaw: Do you know that was my mother’s church for a time?

Dawnie Walton: Are you serious?

Deesha Philyaw: The world is so small.

Dawnie Walton: We went there. Long enough for me to get baptized. I got baptized, and my dad at the time had a carpet and upholstery business that he was trying to like get some customers for so that’s why we went to Bethel Baptist for a short period of time. So, I’m very unfamiliar with Bible stories and I was very curious when you came across the story of Jael and what drew you to it.

Deesha Philyaw: Sure so, I came across the story, not in the Bible, but reading about her story somewhere else. And I don’t remember now where that was, but read about it. And my mind was blown because what it did was describe sort of the viciousness of the crime that Jael commits.

And I just remember thinking, I know that the Bible is a violent book, but I’d never read violence being enacted by women, at all. So, I was like, “I am saving this. I don’t know what I’m going to do with it, but I’m saving this story.” And so, I went to one of those Bible sites online, found it, cut and pasted into a document and sat on it for probably like at least a year and then when I was writing additional stories and I knew I wanted to write some stories around this theme, I knew I was building a collection when I started working on Jael.

And so, what, if somebody named their child Jael, why would they do that? What if she was a 14-year-old Black girl? What would the implications be of her name? What would she be like? And so, in answering those questions, the story started to develop.

Dawnie Walton: And then we’ve talked so much about “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands.” So, I’m going to go to “When Eddie Levert Comes.” And so, this is a collection that is full of incredible names and nicknames. We have Eula, Caroletta, Lee Lee, Tasheta, Miss Mabel, Miss Marita and of course all the biblical names that I’d never heard before that are in Jael.

But in this one, we get the Daughter and Mama for reasons that are very clearly explained in this story. And I was interested… I was wondering if you ever thought about revealing your daughter’s real name. Do you know what it is?

Deesha Philyaw: No, I didn’t give her. She doesn’t, even to me, her name is unknown even to me, but wouldn’t that be a cool thing for the TV show?

Dawnie Walton: Yes, it would.

Deesha Philyaw: A very cool moment. So, no, I don’t know it.

Dawnie Walton: Another thing for the Google Doc.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly.

Dawnie Walton: I’ll put some ideas in there.

Deesha Philyaw: Exactly. Because it can’t just be like Lisa, right?

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw: No shade to the Lisas out there.

Dawnie Walton: Right, and why Eddie Levert? Because let me tell you, our mothers had lots of lusty crushes on men, and Eddie Levert I thought was a brilliant choice, but I’m wondering why him and not, I don’t know Barry White or who else?

Deesha Philyaw: Well, I mean the story is really a homage to my mother and my grandmother and Eddie Levert, my mom was obsessed with The O’Jays and she does have a picture. She went backstage and got a picture with them one time when I was little. And I wish I knew where that picture is now. And so, because she was such a big O’Jays fan, then I became a big O’Jays fan.

And so, the story is an exploration of what it was, like for both my mother and my grandmother to be caretakers of mothers who were not whom they needed them to be. So, my mother was taking care of my grandmother for a time and before that, my grandmother was taking care of my great-grandmother, who had not been there for her. My mother and my grandmother lived together until my grandmother died.

And so, they were physically together. But there were lots of ways that my grandmother wasn’t who my mother needed her to be. And so, I imagined like, what must it be like to be the caretaker and the primary caretaker with no, you know, they did not have relief. There was no respite care that they could take advantage of, but really having to take care of mothers who were suffering and who were in decline without having had their wounds, not even healed, but just even acknowledged, to my knowledge. And so, that was me exploring what that might have been like for them.

Dawnie Walton: I love too that just as there are generations of women in this story, there are generations of Levert heartthrobs. You have Eddie and then Gerald.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s right, absolutely.

Dawnie Walton: So, one of the other amazing things that have happened for this collection is not only is it going to be made into a television show, but it is being published in the UK, in Germany, getting all these translations, and I understand there’s a tenth story in the UK edition.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Can you?

Deesha Philyaw: I was just going to say, to clarify, it’s only in the Waterstones exclusive edition in the UK. If you want the tenth story, you have to get it from Waterstones, but elsewhere in the UK, it’s the same as the original edition.

But the tenth story is a story that I pulled from the collection initially. So, when we went to market with the partial collection, there were six stories altogether, three that I had published elsewhere, three that had been unpublished. And then, it sold to West Virginia and then I needed to keep writing until I got to 35,000 words, however many stories that would be, and as I’m looking at the stories I already had, I just thought that this one story, called “Must Love IPAs,” which is about a woman who is so desperate for a date for New Year’s Eve, she pretends to like IPAs because it’s what’s in this guy’s dating profile and she doesn’t even like beer.

And so, I didn’t love that story. And now in it’s because it wasn’t a very good story, and then I also, wasn’t willing to invest the time and energy to rewrite it. So, I just pulled it and figured I’d put in something I was more excited about. So, then when the UK folks came to me with this possibility of an exclusive story and they’re like, “Hey, you got a story lying around?” Like, actually I do. And so, I got excited then about going back into that story and seeing how I could make it better and how I could make it fit with the collection and be able to hold its own alongside the other stories.

Dawnie Walton: Well, I am very excited to get my hands on it somehow, some way. So last two questions before I let you go because we’ve been talking a long, long time. The hardest part of writing a short story is?

Deesha Philyaw: Reining it in! Reining in that backstory, I’m better at it, but it’s still the hardest part.

Dawnie Walton: And my favorite part of writing a short story is?

Deesha Philyaw: The magic, the discovery to be able to surprise and delight myself.

Dawnie Walton: The magic is a great place to wrap this up. Deesha, this was a treat…

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you.

Dawnie Walton: …to talk about these stories at this level with you. Thank you so much for your generosity in sharing absolutely everything here today.

Deesha Philyaw: Oh, Dawnie, thank you so much.

[Music Break]

Dawnie Walton: And thanks again, everyone for listening. Ursa is a brand-new thing and we want to keep producing great interviews and stories for many more seasons to come. So if you’d like to support the show, leave a five-star review and comment on an Apple Podcasts.And if you’re feeling especially generous, you can become an Ursa Member by going to www.ursastory.com/join, or subscribing inside Apple Podcasts. We’ll use those funds to help pay for another season of Ursa. Thanks, and we’ll see you soon!