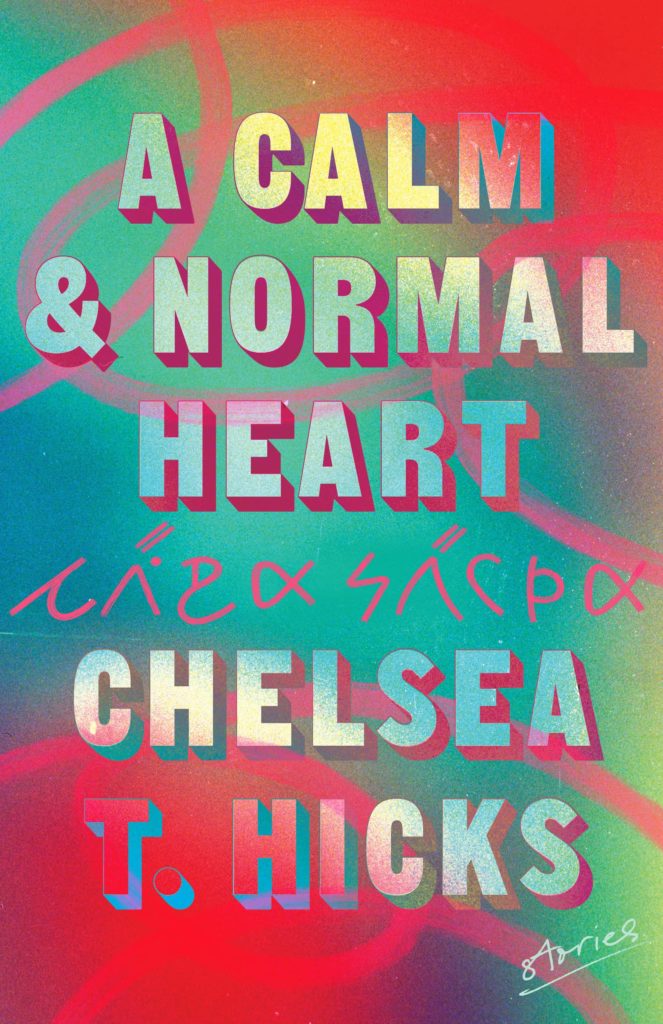

On Episode Five of Ursa Short Fiction, Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton dive into the short stories of the acclaimed new collection A Calm & Normal Heart, with its author, Chelsea T. Hicks.

Hicks is a member of the Osage Nation, and the collection, published in June 2022 by Unnamed Press, also incorporates her ancestral language of Wazhazhe ie (which translates to “Osage talk”). The collection opens with a poem in the orthography, along with the Latinized spelling and English translation.

𐓩𐓘͘𐓲𐓟 𐓷𐓘𐓮𐓬𐓟 𐓷𐓣𐓰𐓘, 𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓯𐓝𐓟?

𐓰𐓘𐓰𐓘͘ 𐓪𐓻𐓶 𐓧𐓪𐓤’𐓘 𐓵𐓣𐓤𐓘𐓸𐓘 𐓬𐓟

𐓲𐓟𐓸𐓪𐓬𐓟 𐓘͘𐓪𐓸𐓰𐓘 𐓮𐓤𐓘 𐓤𐓘𐓵𐓪͘ 𐓲𐓟𐓸𐓪𐓬𐓟 𐓟𐓤𐓪͘ 𐓨𐓣͘𐓤𐓯𐓟

𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓯𐓤𐓣 𐓜𐓟 𐓲𐓣 𐓷𐓣𐓰𐓘 𐓬𐓘𐓸𐓟 𐓩𐓘͘

𐓣𐓵𐓘𐓬𐓟 𐓟𐓩𐓘͘ 𐓤𐓘𐓤𐓪͘ 𐓰𐓘𐓰𐓘͘ 𐓺𐓘𐓩𐓣 𐓰𐓪𐓰𐓘 𐓡𐓶 𐓰𐓘 𐓘𐓬𐓘

𐓤𐓘𐓤𐓪͘𐓰𐓘 𐓷𐓘𐓵𐓶𐓯𐓪͘𐓰𐓘͘

𐓘͘𐓻𐓣 𐓩𐓘͘𐓲𐓟 𐓷𐓘𐓮𐓬𐓟

𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓟𐓲𐓣 𐓰𐓸𐓘͘ 𐓘𐓲𐓣 𐓡𐓣͘𐓟?

my functional heart, where are you?

what turned you into an empty glass

is it that I love the spiders & am like one wherever I go making my house

I have only to wait & all things come to me & therein break their necks

but a calm & normal heart

where does that come from?

About Chelsea T. Hicks

Chelsea T. Hicks is a model, author and current Tulsa Artist Fellow. She is a Native Arts & Cultures Foundation 2021 LIFT Awardee and her writing has been published in McSweeney’s, Yellow Medicine Review, the LA Review of Books, Indian Country Today, The Believer, The Audacity, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. She is a past Writing By Writers Fellow, a 2016 Wah-Zha-Zhi Woman Artist featured by the Osage Nation Museum, and a 2020 finalist for the Eliza So Fellowship for Native American women writers.

Her advocacy work has included recruiting with the Virginia Indian Pre-College Outreach Initiative (VIP-COI), Northern and Southern California Osage diaspora groups, and heritage language creative writing and revitalization workshops. She authored poetry for the sound art collection Onomatopoeias For Wrangell-St. Elias, funded by the Double Hoo Grant at the University of Virginia, where she was awarded the Peter & Phyllis Pruden scholarship for excellence in the English major as well as the University Achievement Award (2008-2012). The Ford Foundation awarded her a 2021 honorable mention for promotion of Indigenous-language creative writing. She is planning an Indigenous language creative writing Conference for November 2022 in Tulsa, funded by an Interchange art grant.

Episode Links and Reading List:

- A Calm & Normal Heart (2022)

- Of Wazhazhe Land and Language: The Ongoing Project of Ancestral Work (Lit Hub)

- Osage writing system and orthography

- There There, by Tommy Orange (2019)

- Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino (1978)

- Night of the Living Rez, by Morgan Talty (2022)

- America Is Not the Heart, by Elaine Castillo (2019)

- Men We Reaped: A Memoir, by Jesmyn Ward (2014)

- Heads of the Colored People, by Nafissa Thompson-Spires (2019)

- Milk Blood Heat, by Dantiel W. Moniz

- Nobody’s Magic, by Destiny O. Birdsong

- You Don’t Know Us Negroes, by Zora Neale Hurston

More from Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton:

- The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, by Deesha Philyaw

- The Final Revival of Opal & Nev, by Dawnie Walton

Support Future Episodes of Ursa Short Fiction

Become a Member at ursastory.com/join.

Transcript

Chelsea T. Hicks: I can be a bit of a literary slut, where I read everybody and like a lot of things.

Deesha Philyaw: You are highly quotable. I can’t wait for the soundbites from this episode.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Oh my gosh.

[Music]

Dawnie Walton: Hey y’all, I’m Dawnie Walton.

Deesha Philyaw: I’m Deesha Philyaw.

Dawnie Walton: Welcome to the Ursa podcast, a celebration of all things short fiction. On this podcast, we interview authors, discuss collections and stories we love, and shine a light on new writers and those who never got their due.

Deesha Philyaw: And at Ursa, we’re not just talk, we’re publishers too. Over at ursastory.com, we’ve created a new home for short fiction from some of today’s most thrilling writers, as well as emerging voices, with stories you can read on your phone and audio stories that you can listen to right here in your favorite podcast app.

Dawnie Walton: We’re doing all of this with support from you. Become an Ursa Member today by subscribing to an Apple Podcasts, or by going to ursastory.com/join.

So today we are thrilled to be in conversation with Chelsea T. Hicks, whose debut collection, A Calm & Normal Heart, published June 21st by Unnamed Press, contains 12 astonishing stories that Brandon Hobson has called “full of quiet truths and wry soulful secrets.”

And I also have to say, I agree with Kali Fajardo-Anstine, author of Sabrina and Corina, who has said this collection is quote, “Unlike anything I’ve read before.” She continues, “At the intersection of tradition and technology, past and present, these vivid and absorbing Native characters fill the pages of this extraordinary debut with tenderness and humor.”

Deesha Philyaw: And a little more about today’s guest. Chelsea T. Hicks is a model, author, and current Tulsa Artist Fellow. She is a Native Arts & Cultures Foundation 2021 LIFT awardee, and her writing has been published in McSweeney’s, Yellow Medicine Review, the LA Review of Books, Indian Country Today, The Believer, The Audacity, The Paris Review, and elsewhere.

Dawnie Walton: And this is very exciting: She’s planning an indigenous language creative writing conference for November, 2022 in Tulsa, funded by an interchange art grant. Chelsea, welcome to the Ursa podcast!

Chelsea T. Hicks: Thank you so much. You guys are taking my breath away.

Deesha Philyaw: Back at you. Right back at you.

Dawnie Walton: Yes, back at you.

Deesha Philyaw: And for those who haven’t read the book immediately after the title page of this collection before the table of contents, and the author’s note, there is a poem in Wazhazhe ie, the language of the Wazhazhe people, and then it appears in English. And Chelsea, we would love to hear it in the original and in translation. Would you read that for us?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yes, I’d be delighted. Okay.

𐓩𐓘͘𐓲𐓟 𐓷𐓘𐓮𐓬𐓟 𐓷𐓣𐓰𐓘, 𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓯𐓝𐓟?

𐓰𐓘𐓰𐓘͘ 𐓪𐓻𐓶 𐓧𐓪𐓤’𐓘 𐓵𐓣𐓤𐓘𐓸𐓘 𐓬𐓟

𐓲𐓟𐓸𐓪𐓬𐓟 𐓘͘𐓪𐓸𐓰𐓘 𐓮𐓤𐓘 𐓤𐓘𐓵𐓪͘ 𐓲𐓟𐓸𐓪𐓬𐓟 𐓟𐓤𐓪͘ 𐓨𐓣͘𐓤𐓯𐓟

𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓯𐓤𐓣 𐓜𐓟 𐓲𐓣 𐓷𐓣𐓰𐓘 𐓬𐓘𐓸𐓟 𐓩𐓘͘

𐓣𐓵𐓘𐓬𐓟 𐓟𐓩𐓘͘ 𐓤𐓘𐓤𐓪͘ 𐓰𐓘𐓰𐓘͘ 𐓺𐓘𐓩𐓣 𐓰𐓪𐓰𐓘 𐓡𐓶 𐓰𐓘 𐓘𐓬𐓘

𐓤𐓘𐓤𐓪͘𐓰𐓘 𐓷𐓘𐓵𐓶𐓯𐓪͘𐓰𐓘͘

𐓘͘𐓻𐓣 𐓩𐓘͘𐓲𐓟 𐓷𐓘𐓮𐓬𐓟

𐓡𐓪𐓷𐓠𐓤𐓣 𐓟𐓲𐓣 𐓰𐓸𐓘͘ 𐓘𐓲𐓣 𐓡𐓣͘𐓟?

my functional heart, where are you?

what turned you into an empty glass

is it that I love the spiders & am like one wherever I go making my house

I have only to wait & all things come to me & therein break their necks

but a calm & normal heart

where does that come from?

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you. And so we know that A Calm & Normal Heart is the title of the collection. Can you talk a bit about how this poem sets the table for the collection?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yes. So, that phrase na^tse wacpe, It can mean, a strong heart, or a calm and normal heart. And it can also refer to a band of Wazhazhe people called Heart Stays. And I think I’m really interested in the collection, in this question of who stayed home, and who left? And why? How did that create divisions?

Where is home? What is home? And what is a person trying to make a home have to do to achieve that? And is there a type of a heartlessness in setting boundaries and growing that changes oneself from the training of home? So I think that this poem sets up some of those questions that I try to investigate throughout the stories.

Dawnie Walton: We’re going to get really deep and try not to do too many spoilers, because I know a lot of people are still going to be so curious about the collection after listening to this. But I would love to know a little bit more about you, Chelsea, and your personal journey to becoming a storyteller. When did you first start writing stories? And when did you know that this was the right path for you?

Chelsea T. Hicks: The first short story that I wrote, I was in a workshop at the University of Virginia. And prior to that, I had written poems, like a lot of teenagers trying just to process one’s emotions. So I was really nervous to write a short story, but I really loved reading and that had kind of been my refuge as a teen.

My dad ran a construction business, and he wanted to instill work ethic in us. So one of the ways I could get out of working was by reading, because he really glorified the intellectual mind. So, I just was an addictive reader and I thought, I’ll try to write a story, but it took me a really long time before I felt like I found anything close to my voice because the kind of ideal of short stories that I experienced in workshops was very subtle, and I think white—very like, not much happens, it’s very delicate.

And I mean, I had taken this class with Ann Beattie, I remember taking class with Ann Beattie and reading a lot of Raymond Carver, and I always felt like I’m well-read maybe in the so-called canon, but for me to do what I needed to do to have my voice out there, I feel like I had to kind of come to my wits’ end in trying to assimilate over, like, about 12 years. And it wasn’t until, I had written a novel and had an agent shopping that novel around and got feedback from different publishers saying, This just doesn’t seem like a first book.

And I took it to mean like, your subject matter is too specific, it’s not recognizable enough as Native and you need to open up this niche of literature first, before we can recognize you. And I thought, Okay, I guess it’s just time for me to say what I want to say very directly and forget all of this that I’m trying to supposedly assimilate toward.

Dawnie Walton: Wow. That leads really beautifully actually, into the next question that I have, because you studied creative writing. I mean, you have a couple different Master’s. You have Master’s in creative writing from both UC Davis, and what I’m very interested in is your studies at the Institute of American Indian arts, because I’m a graduate of Iowa, and I’m very grateful for everything I learned there, but I often say to my friends, I would love if there were an HBCU that had an MFA program in creative writing, because I do wonder what writing in the complete context of my community, how that would enrich my writing or inform my writing. And so I’m wondering how it affected you, how writing in the total context of Indigenous community helped you to develop your voice and your stories.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah, it was something I needed, sorely, because I think growing up mainly away from the Osage Nation in Southern Virginia and staying sometimes with my iko, or as we call grandma, in Bartlesville, sort of like a rez border town, I had enough cultural and tribal connection to not feel like somebody could tell me I didn’t belong or that I was an outsider, but also enough disconnection that I was still treated sort of like, Oh, you’re not from here, when I was home in the Osage.

And so when I went to IAIA, I did so because I think three or four people were encouraging me to, one, a mentor of mine at UC Davis who also taught at IAIA, Pam Houston, and she introduced me to Tommy Orange and Terese Mailhot and they were just graduating then. And Tommy encouraged me to go there as well as, a cousin, or not a cousin, but a culturally like a cousin, a friend, Ruby Hansen Murray.

So these people were all urging me, Go there, go to the Institute of American Indian Arts. And I was kind of like, Why? But I mean, I said to myself, Well, I guess why not? Let’s see what happens. So, I remember being there. There would be these charged kind of political caucus-like discussions around things like Indigenous language, Native diaspora, and reservation politics around things like representation. And so that was exciting to me, intellectually, to have basically these debates going on.

And then, writers like Sherwin Bitsui, who writes in Diné and Navajo language. I remember this craft talk that he gave about finding ways to embed your cultural lessons within the form of poems or of writing, and it was so impactful to have a sense of Native community, and that I felt like writers there really supported each other, wanted each other to succeed. It felt like a family. And I made the intentional decision to choose mentors who were all Native women, because my dad is my Native parent. And so I felt since my iko had passed away, that was something I was lacking, and I just needed mentorship by Native women.

And that program really provided that in a way that felt more overall like human and familial to me even than intellectual. So, it was just a really healing experience. It challenged me to think about what does it mean to write something that has my community’s best interests at heart and is still recognizably Native in a way that can command American attention?

Dawnie Walton: Yeah, that’s so beautiful. And I’ve had the experience of being in workshops with other Black women and even other women of color. And there is sort of a freeing there, and there is a support to write toward your intended audience, and to not fall into the trap of overexplaining or any of that. And it’s just a really beautiful and freeing thing. So what an amazing experience that must have been.

Deesha Philyaw: And so Chelsea, can you take us from those experiences, and sort of further along the journey to where we are now with the publication of your collection.

Chelsea T. Hicks: I guess there was kind of a pivot point in my last semester at IAIA. I had been working on this novel, it was called Iko. It was obviously about my grandma, which I’m starting to feel is a Native cliché, anybody beginning a poem with my grandmother. I…

Deesha Philyaw: We get that too.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah,

Dawnie Walton: Yeah, actually the new thing I’m working on starts with a grandmother. So yes.

Chelsea T. Hicks: You gotta love it, it’s the bedrock of the community. It’s the carrying on of cultures, our ancestors. But I was just noticing that the other day, because I’m working on this zine, Wazhazhe reconnection zine with my cousin. And there was several things that started with my grandmother and here I am–my grandmother novel.

Yeah, so I had gotten an agent, while I was—I guess still at UC Davis or shortly thereafter. And I had this agent, through my time at IAIA, but like I mentioned, I had gotten feedback from publishers and I decided to switch what I was working on, to be a collection of short stories instead of a novel.

And I wrote most of these short stories while I was living in Pawhuska, my tribal district in the Osage Nation. And I was working Daposka Ahnkodapi, which is our language focused tribal school. And I was living alone. It was a lonely period. I had gotten out of a long relationship in California and kind of just moved to Oklahoma for this job.

And I was really focused on the language. So these stories, I just kind of felt like I had nothing to lose. I just write whatever I felt, whatever I wanted to say. Not that I didn’t care, but I just kind of felt beat down. And so I just didn’t feel like I had much to lose, and I just kind of wrote things that usually I might feel is a little too inarticulable or sensitive.

So when I graduated, I was reworking the novel again, but with my agent, we had this conversation, and she was like, “Well, would you just like to sell the stories instead? Should that be your first book? What do you want to be your first book?” I’m like, “Yeah. Okay. Well, the stories feel alive for me. I’m thinking about these things. I’m living some of these themes, so let’s go ahead and do that.” And it sold right away. I had just two meetings, one with Nadxieli Nieto of a press in New York, a new imprint. And then one with Chris Heiser, who was the editor for this book. And he had considered making an offer on the novel prior to that.

And I thought, you know, I want somebody who stands beside my work as a whole and is accepting toward my writing and what I want to do on my own terms. And so I felt like Chris had that. And also I think that my stories were just a little bit, maybe hateful seeming toward white men. And he was a white man and I think my agent was encouraging me to talk to everybody, be friends with everybody, calm down. And so…..

Chelsea T. Hicks: He was the best choice, yeah.

Deesha Philyaw: So in the author’s note to the collection, you set forth a really beautiful intention. Can you talk about the language of these stories and how it builds toward that intention?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Right, I really. Wako^bra. I want it for them. Wazhazhe nikashi wako^bra. I want it for Osage people to have a revitalized language. I’m passionate about our language. There are other people, you know, one of my teachers, Chris Cote, who is a… I would call fluent speaker, although I guess technically by linguistic standards proficient, and many others — Talee Redcorn is one who comes to mind, my teacher, Herman “Mogri” Lookout—that are really passionate about the language and I’m in a community of learners, but as a whole, I don’t think that the Wazhazhe people feel empowered and resourced enough to revitalize our language, which is really hard. And that can create shame and feelings of failure as well as unrealistic expectations of people who have a lot of burdens on them. If they’re a single mother or whatever it is, that it’s not realistic for them to kind of learn this second language as adults, even if they grew up in a household where they were hearing select Wazhazhe ie phrases, like Wano^bre kqu pi, “Come to the dinner table and eat.” They’re not speakers, proficiently.

And so I thought, Well, what can I do that celebrates our language without overdoing it and creating too much pressure? You know, I’ve been working on a collection of poetry in Wazhazhe ie, but I thought something a bit more meta that includes language somewhat, but just tries to give a reflection of kind of what’s going on with the language now, rather than this picture of a revitalized language or this picture of fluency.

So yeah, I just wanted to, not agitate things, but promote growth by — you know, when you build muscle, they say, you know, you break the muscle just a little is what causes it to grow. That’s what I wanted to do with the language. And hopefully that the kids who study at that Daposka Ahnkodapi school, you know that when they’re maybe like in eighth grade, ninth grade, and they have a high school open, that they would be able to use this book in curriculum. And just to have something in our language that is written and contemporary, since we did decide as a tribe to make it written, which was recent in the ‘90s.

I really hope that what I’m doing with the language here is sensitive and compassionate. And also I do want to be supportive, to expand the ways we think about our language in that it’s not just for ceremony, and it’s not just for language class, it can be in literature and ever-growing in our daily living lives’ conversation.

Dawnie Walton: And Chelsea, I love the fact that you say in your editor’s notes, that there’s limited recognition of the Indigenous characters that are part of Wazhazhe. And so you do use the Latinized spellings within the stories, but on the cover and in the chapter titles, you are using that orthography, which is actually a word that I’m just learning from you from this editor’s note.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: Did you always know that you wanted to include the orthography in some way in the collection? Or is that something that kind of came in later in the process?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Well, I did want to include it, but I didn’t think it would be possible. I recently learned that one Wazhazhe artist, Dr. Jessica Harjo, who has an artist brand called Weomepe, has been creating different stencils and fonts. And these are in the process of being integrated so that we have more options, but I couldn’t get the orthography to work in Word on my computer, although I could get it to work in Google Docs and on text.

So, I just didn’t know how it would be possible to get my editor and the printmaker to have the access, when I would call the Osage Nation IT or the language department. And we would go through for an hour or two, how to get it to work on Word. And I think somebody eventually told me it’s not compatible with this certain update to Word.

And so I thought it just wasn’t possible, and when Chris Heiser, my editor, told me that, the art directorJaya Nicely might be able to paint it, I was thrilled and that actually came about because he was pushing me, “Why are you not translating this conversation in ‘Tsexope’? why are you going to antagonize your readers like that?”

And I said, “No, I have to keep this language without a translation. Not only as a pedagogical device, but to encourage every reader to wonder to themselves that seed of wonder, well, what languages do I stand to inherit? What languages might I one day be learning or speaking or revitalizing,” and he’s like, “Okay. Well, if that’s how you feel, would you like to have the orthography?” And I’m like, “Yes, that would be wonderful.”

Dawnie Walton: I love that he was in support of that. That’s great.

Chelsea T. Hicks: He was, yeah.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

[Music]

Dawnie Walton: So, moving into sort of the themes of the collection, because there’s so many, but there’s a couple that I picked up on, that I would love to talk with you about. So one of them is dreams. So dreams play such a role in a lot of these stories, and I’ve always found it very difficult to write them, dreams and nightmares, because you have to capture them both as convincing and surreal at the same time.

And so I just kind of want to pick your brain as a writer, what is the importance of dreams to your characters first of all? And how do you approach writing them or getting them on the page?

Chelsea T. Hicks: So the importance of dreams to the characters is I think that people who, for whatever reason, they’re not able to choose explicit, direct processing — maybe it’s because of their family dynamic at the time, or because of the constraints on their life, that they’re not necessarily intentionally journaling through everything, they’re not necessarily in therapy, or even if they are, they need more capacity to process things. And you know that concept of dream work.

So I think it’s the dream work. It is like a pragmatic subconscious response to pressure and stress, and I think for Indigenous people and BIPOC people, more broadly, that dreams can be like this key that I kind of think can help us live. They provide clues toward what we might do next and like, cultivating the muscle of remembering the dreams, gives these characters the ability to kind of troubleshoot their own life. And then how to do it craft-wise — I remember talking to Brandon Hobson, who’s my thesis mentor at IAIA, I told him, I know in his writing that he does some stuff with dreams and his books are really sensory details, sensually oriented.

And so I was asking him, “What do you think? I really trust your opinion. How can I bring in dreams more?” And he told me to read an Italo Calvino book, something about cities in the title [Invisible Cities]. I will have to look up what it is. What I noticed there was that they were reductive stories. I don’t love that word, but what I mean by it is highly compacted and with no extraneous detail. So I tried to take the dreams and make sure that they’re related to the sequencing of the events of the story.

But then besides that, then I just really boil them down to some type of nugget of what the dream was about. And then it doesn’t take up so much room, because times that I had tried to write, really write into the dream at length and make the dream the center of the story, I don’t know if that’s something I could pull off yet, so I didn’t try to do that, and I might like to do that in further work for sure. But here, I just used basically summary, and I felt like I could get away with anything if I use highly compacted reductive summary

Dawnie Walton: I have to try that.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah.

Dawnie Walton: I feel like I remember… This is not literary, but I remember watching The Sopranos, for some reason and they always did dreams very well, I thought, where was like, meaningful to this story and yet really bizarre and strange.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Right.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

Chelsea T. Hicks: I’m with you on that, I’m learning that.

Dawnie Walton: So, the other theme that I noticed sort of recurring in the stories was about music.

You have characters playing Kendrick Lamar, Thurston Moore, Rolling Stones, and the story, “My Kind of Woman” has musicians as the main characters. And then the first story in the collection ends with the narrator saying, “But one more song.” So, as someone who’s interested in the influence of music, I’m so curious how it inspires you.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Oh, my word. Well, the short answer is that I used to be in bands and have bands, and I would be the frontwoman and the keyboardist and the lyricist, if not the songwriter sometimes. And when I lost my last band in I think 2017, it was so shattering to my coping mechanisms that I would use that band practice time to… and we would write together live in a rented space.

I lost that time of just kind of like, howling and singing and emoting. I just put it more into my writing, that at least my characters would listen to music and be in bands. So, I was talking to Morgan Talty, a debut author from Tin House with the short story collection Night of the Living Rez, we were doing a conversation interview the other day, and he was telling me that he felt like music and pop culture references in Native literature right now, were like a recurring Native motif. And he was referencing Tommy Orange’s There There, and I was…Maybe I’m influenced by that. I think that when I’m trying to signal who characters are, I feel that music is so personal.

You know, it’s what you listen to when you’re comfortable, when you’re joyful, it’s not necessarily something— these characters, aren’t telling someone what they wish they listened to or what they would want to seem to be a person who’s listening to. They’re actually listening to this stuff. And I feel like it tells who they are.

Chelsea T. Hicks: I think it’s just fun to learn about new music from reading books. Talking about that, Dawnie.

Dawnie Walton: I will say that I looked up that Thurston Moore song, because I’m a Sonic Youth fan and I’m not too familiar with his solo work, and so I did play that. I played that video.

Chelsea T. Hicks: What did you think?

Dawnie Walton: It was really interesting, yeah.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah, like that character, the one who selects the song, like a Native designer, sort of a niche, like pretty cool, like sad boy hipster kind of thing. So, I’m okay, I don’t necessarily listen to this, but this character does.

Dawnie Walton: Right, I love that.

Deesha Philyaw: So let’s jump into, talking about some of the specific stories in the collection. The first one I’d like to talk about is “Tsexope” and I’m feeling very fancy, because I said it, I think I said it right.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah, that was beautiful.

Deesha Philyaw: Thank you. Fishing for compliments.

Chelsea T. Hicks: You deserved it.

Deesha Philyaw: There’s a bit of satire in this story, and it’s a story about the film industry. In the community where the story takes place, there’s a movie that “was telling one of our stories at the hand of a big name director with a cast of equally famous celebrities.” Why did you choose this as the context and backdrop for the flirtation that unfolds between the two main characters? And why did you choose this as the story that kicks off the collection?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Well, I’ll start with the second question of why start off the whole collection this way. And I think it’s because individual tribes and Indigenous groups, sometimes suffer from a lack of awareness or even being known as existing because there’s so many different tribes. And typically in my experience, like people probably have heard of Cherokee and Navajo. And if people haven’t heard of many more tribes than that, they definitely haven’t heard of Osage or Wazhazhe people.

But in, I think 2016, David Grann wrote a book called Killers of the Flower Moondramatizing the rise of the FBI and how that related to the Osage Indian oil murders. And those were in the 1920s in Osage County. So, this is a double edged sword because it’s good for Osage people to become known about. And for our existence to be not gaslighted, basically, that we don’t know who you are, therefore, you don’t exist.

Chelsea T. Hicks: But then at the other end of it, of course, lots of people get activated by hearing traumatic things talked about that aren’t talked about necessarily that often in our communities.

And then on top of that to have this told by I^shdaxi^, non-Native person. So it’s just really complicated, and I think that Wazhazhe people have worked really hard, a lot of the time unpaid, sometimes paid, to promote the accuracy of our representation in Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon movie, which will be coming out.

And, I know many of our districts would have dinners to entertain the director in cast or one woman, Addie Roanhorse, she was a consultant working very hard, culturally consulting on the film, and many Osage people—I should say some, but in a way, it feels like many, starred in the film.

So it’s not like a completely black-and-white issue. And a lot of people would take a stance, like for, or against the film, like boycotting this or that, or else pro the film, because many times if they are cast in it or one of their family members are. And so I think that leads into the question of why is it the backdrop for the flirtation, is like, one of the ways that in a Osage flirtation, one of the parameters around that might be, Who’s more Osage or who’s the most Osage?

And if that question is too, you know, bald and rude and direct of me to state. I would say that I only do so in order to introduce other topics, around this us-versus-them mentality that can come even within the own tribe, and is more individualistic than collective in thought.

And so for these two characters to flirt by talking in Osage and to ask each other, “Oh, are you in the film?” “No. Are you?” It’s just kind of a way of them establishing their similarity toward each other. And like, what’s their…what’s that word? Positionality. Like they’re situated such that their relationship.

It’s not really a power imbalance. If one of them is more Osage than the other, or one of them is a California Osage and the other Osage wishes they could get out of the rez. It’s like, no, these two they have enough in common that they can just slide right into a relationship real quickly.

Dawnie Walton: I love that. Now, so many of these stories are contemporary, but….. I think this is my favorite in the collection. “A Fresh Start” is actually set in 1956. Let me tell you, I loved Florence. Florence feels like a woman on the edge of a breakdown, trying to hold this family together. And I was so thrilled when later in the collection, Florence and her family appear again in a story that appears later in the book called “Full Tilt.”

So I find Florence fascinating, even in the gap in the year that happens between the two stories. And I would love to hear….. I just want to hear you talk about her and how she came to you, how you developed her, how you see her.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Basically she was the character for that novel that I had mentioned, and so she’s kind of that iko person, the grandma person. And, so growing up, I had this close relationship with my iko where she was very kind of elegant and there was all this tea time and like velvet and I felt like she just represented this romantic kind of Venusian ideal to me of, like, reading etiquette books. And it was so funny because of course she had grown up going to the, Paola Indian boarding school in Kansas. And so a lot of that was from–I guess like a violent backdrop, but for me, I just thought like, “Oh, wow, she’s so fancy.”

But my aunts and my dad and my uncles would tell me these horror stories about how she would beat them and that she was, unstable, that she would have mental, multiple hospitalizations, suicide attempts and that she was totally unmoored woman.

And there was this big division in my family of why would you even let your daughter have a relationship with this woman? And so when she died, it was 2015 and I was working in a French-inspired pastry shop in San Francisco in the Ferry Building, like shelling pastries with this wardrobe that was like, you have to wear pink, flowery dresses, and you should not be seen in the leggings. And it just reminded me of her.

And I loved being there because it reminded me of my grandmother, but also, my vision kind of blacked out. And I was not really eating anything except for bits of macarons. And I was totally confused and very mentally unhealthy. And so I started writing about this Florence character.

And I was in Yiyun Li’s workshop. And Yiyun Li was so happy because I had been writing this kind of me, lightly, veiled me, almost having a breakdown in this pastry shop. And she confronted me. She was like, “Why are you writing this?” And I’m like, “Well, I miss my grandmother. And she’s like, “Well, then just tell that story.” And I was like, “Okay.”

And so I did, I started telling Florence’s story and it was really just me questioning, What would cause a woman who’s an orphan of the Osage oil murders to first of all, be able to live and survive a whole lifetime, but do so in a way where she’s trying constantly to get a better life for herself and her children, she has internalized racism, or if it’s in part, and if it’s not only internalized racism, she’s also just assimilated to where she’s lost a lot of her functional tribal collective community connection.

And what would her life look like? How did it come to be that, you know, I was raised the way I was and that my dad is the person he is. And it was just me writing into those big familial confusions. So Florence, yeah, I’m really thanking you for saying that you love her because that was what I heard from publishers was like, “This character is just not likable. We don’t like this character.”

Deesha Philyaw: We love a messy woman. We love a….

Dawnie Walton: Oh my goodness, that’s my favorite thing. I mean, how could anyone read that character and not have empathy?

Deesha Philyaw: Well, I think that, because we hear this from other writers in publishing and I certainly heard it with the mother character in my story, “Peach Cobbler,” that there is a resistance to mothers who aren’t motherly, who aren’t a hundred percent kind who, who we can’t deify, and that’s such a loss. And because I think many of us are hungry for literature that features those mothers, you know?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, okay. So please tell me, you’re still working on this novel.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah, well… I mean, Chris Heiser, my editor, he does want me to work on it again, so maybe. But I worked on it for five years and I know that we writers work on things for ten years and longer. So I guess we’ll see…

Dawnie Walton: And in the meantime, we have these gorgeous stories, which we would also take more of.

Deesha Philyaw: Absolutely. So, “A Fresh Start” was also my favorite story, and I do love Florence as well. I loved that the story was so cinematic. And the dialogue in particular was incredibly evocative of that era that the 1950s, late fifties. And then there’s this really sharp dialogue. And through that dialogue, I got to know Florence and the other characters. And I’m wondering how you approach dialogue as it relates to characterization.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Okay, I heard the initial teachings of dialogue can reveal something about the character. It can move the story forward. And then another one is, people don’t necessarily listen to each other when they talk to each other. Sometimes they’re not really paying attention to each other.

And so those are the things that I received as guidance. But for me, particularly, I think that I was just interested in the way people talk like, what they sound like, and the funny things that they say. The way that we as people are, we are trying to, not seduce each other with what we say, but be winning, get our way, get along, be agreeable, antagonize.

And so I think that I’m thinking of the moment on the phone when Florence is talking to her brother and the way that she’s just talking in these tiny little snippets, like, “Oh.” I can’t even remember exactly some of the dialogue, but I remember that just like conveying the mood, the moment through kind of the art of dialogue, it’s a way of presentation. It’s a way of expressing the self.

And I also love the dialogue tag so much because I can create an image through what someone’s doing, and then what they paired with their words, almost like it was like an artistic offering. They’re setting down the gold lamé pumps and saying, “Would you like pie?” And it’s just an aesthetic offering.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Deesha Philyaw: So let’s talk about “By Alcatraz,” this one takes place at a friendsgiving hang where the narrator unexpectedly finds allies among a group of Black friends and they watch Blade Runner together. And what inspired this story and why Blade Runner as the movie?

Chelsea T. Hicks: I don’t know, Blade Runner just seems like—it’s this cult movie that is about cool misfits and people who…I mean, it’s set in a future world, and I never understood the movie and I’ve watched it a few times myself and I still don’t fully understand it. And so I think that, to me, it just represents that time that at least I had in college where, in the way—in kind of the culture in which I grew up, it was almost like, it felt like a sin to be cool.

And so watching cool movies and not understanding them was like a lot of what I did in college. And so now, I feel like most of those movies that I would’ve seen at that time, yeah, I get it. I know what’s going on, Amélie, Fight Club. With Blade Runner, I’m just like, what?

Dawnie Walton: I’ve never seen it, but you’ve got me curious now.

Chelsea T. Hicks: I mean, I don’t even know if I can recommend it. It’s that there’s this one woman in it who starts it off and she’s wearing like this raccoon face paint all over her, and it’s just very weird. It’s very aesthetic. So it was all about the aesthetics and in-aesthetic. The story itself, I wanted to write something that was set in San Francisco over Thanksgiving break, because I wanted to bring in Alcatraz somehow.

And I just thought about how Native people, when outside of community, can be lonely and like not really fit in with anybody exactly. The story actually like where it actually comes from was an exercise Tommy Orange had given when I was at IAIA and he had become faculty there.

And he said, “I want you to write a door into a story, something that you’ll polish, that’s an opening for you. So write about something that you’ve never written about, that you really think would be an accessible entry point for a lot of people.” And I just started writing about various exes throughout my whole life. From the time of like, I’m talking about like nine-year-old boyfriend exes.

There was this one guy, this character Darren with floppy hair. And I just had this idea of the guy who kind of doesn’t get it, but is sweet in a way. And just like, what happens when you’re trying to get along with somebody who doesn’t really get you and isn’t really compatible with your background.

And so, the Black friends are kind of… she realizes like, Oh, maybe I would be better off by spending more time with people who also struggle with being full members of this American community. I have more in common with maybe people that I wasn’t trying to seek out and maybe it would be better for me to just stop trying to pursue Darren and open it up to like those who might have some more commonalities.

Dawnie Walton: “Superdrunk.” So that one starts off. There’s an epigraph from Luster by Raven Leilani, which I feel is becoming of kind of a contemporary classic of sorts. And then there’s a later story that has a quote from Louise Erdrich and it just had me curious about the other contemporary writers that you feel your work or your voice are in conversation with.

Chelsea T. Hicks: I think Elaine Castillo, from America is Not the Heart. I feel like she, well, she uses Tagalog and Ilocano, so she’s got language in there. And I think that both of your books for sure, because when I look at Dawnie, the way that you use music, and what I would say is like, the journalistic aspect, where it’s this virtuosic challenging toward what is real and what’s fiction. I find that’s something that I really believe in, is hybridity or the inherent suspicion of genre.

And then yeah, Deesha, for your characters, women who totally explode what a culture is supposed to be seen as, and what it’s supposed to be both from the inside and outside of this idea of like church women are supposed to be a certain way, but actually they’re queer or they have very, very deep complex inner lives that are beyond anything that the Bible can really help you with. And so a friend of mine…

Deesha Philyaw: Wow, thank you. I did that?

Dawnie Walton: My head has grown seven times its normal size.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Well, now it’s the right size. No, but my cousin told me that she thought that it was like… She said, “Your writing style is like, it’s the seedy underbelly of Native women.” I was like, “Oh, okay.” She was like, “Or your relationship towards your readers is like a drag queen where you seduce them, but you also roast them. And you’re inviting, but also difficult.” And I was like, “Oh wow, I don’t even know if I can take that and accept that compliment, but I would aspire to it.” And so…

Dawnie Walton: That’s amazing.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah. Just like anybody who’s totally trying to, I guess, go all the way or really push something past its usual boundaries. And so who I’ve been reading, lately that fits that…I’m going to open my Kindle really fast. Because I can be of literary slut, where I read everybody and a lot of things.

Deesha Philyaw: You are highly quotable. Can I just say you’re highly quotable? I can’t wait for the sound bites from this episode.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Oh my gosh. Okay. I’m just going to tell you a few of the ones that I’ve….I can’t analyze it further than to tell you that I read it and adored it and it was inspiring to me and generative. So, Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Yes.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz

Deesha Philyaw: That’s our homegirl…

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

Chelsea T. Hicks: She’s so great. I’m just a fan. Let’s see, who else? I have been enjoying Nobody’s Magic, by Destiny O. Birdsong

Dawnie Walton: Destiny, yes. That is incredible.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah. And she was a poetry teacher at Tinhouse workshop I took and what I just taught to my students this whole semester and what we went over the whole time, was Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward. It was so good. I’m really. Here’s what Jesmyn Ward has me on right now is like, you know, I have this ambition, like many writers to one day, despite everything do the Stegner Fellowship. And I try to analyze like, who has done that, and if I could do the guesswork of what book they published after, like what did their proposal really entail?

And I feel it’s that there’s a project proposed that takes everything you have and emotionally and intellectually with research. And you have to be up to that work, that something that matters to you so much, that you would give everything to it. And so I want to find what that project would be for me.

Dawnie Walton: Whew, that’s intimidating.

Chelsea T. Hicks: It is, but it’s at least food for thought, but we don’t have to answer these questions this year, or even in the next five years. They’re just there, like on the back burner.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah.

Deesha Philyaw: So let’s talk about “Wets’a.” This story, as with some of your others, features an intergenerational cast of characters and it on, I think it’s on two pages, there’s an image that’s composed of X’s and I’s, and the images, this image represents a painting that the main character owns, and the X’s and I’s represent the generations that have come. The character says these are the generations that have come before me. And so I’m curious about the genesis for this story, and I’m also interested in the role that ancestors and elders play in your storytelling. And you’ve talked about your grandmother for example, can you speak to that a bit more broadly?

Chelsea T. Hicks: So the ancestors, when I started learning Wazhazhe ie more intensively, which happened starting in 2016, when this Nimipu writer and translator Inés Hernández-Ávila challenged a group of me and other Native students in one of her workshops at UC Davis, she said, “I have a message for, you all” and the writers in the state of Oaxaca in Mexico, “Why are you not writing in your languages?”

And I was like, “Oh my gosh, I don’t know.” And it really made me think, and you know, my iko passed away shortly thereafter. And when I started learning, and especially as I started learning more intensively, I started having dreams of my ancestors, telling me what to do. And they would tell me these crazy things that I did not want to do.

And I was like, “Oh, my gosh.” And, so I just started thinking about them a lot more like individual ones of them, trying to be inclusive of them. Who is everybody? Who are the groups of people? Do they get along? What’s my responsibility? Where am I making reparations toward my ancestors’ actions? Where am I building on their work? Where am I elevating them?

And it was just something that I think that I experienced sort of like a loss of faith, because when that band broke up, they were all pastors or youth pastors or music pastors. They were all Christians. And they had told me, you don’t need to be writing in Wazhazhe ie. They weren’t telling me “that’s pagan” exactly, but I had heard that before a lot. And so I just kind of felt like I couldn’t…

And I have an essay more in depth about this coming out in Lit Hub, but I just had a worldview, like, earthquake moment. And so the ancestors were the people that imaginatively, subconsciously and spiritually that I was thinking about to get me through that.

And so that’s how my ancestors came into these stories so much. And “Wets’a,” I was thinking about fashion, really, and how there’s not like a Native Fashion Week in the United States, even though this is Native land, and Native people…Like at this year’s recent Met Gala the first Monday in May, we have thankfully, Quannah Chasinghorse and there are indigenous designers that are getting more notoriety, like, Jamie Okuma, and Orlando Dugi, and Lauren Good Day and many others. But there’s so many, and there’s so little recognition that usually when there’s Native inclusion in an event like Korina Emmerich with EMME Studios at the fashion event, back in the first part of Met Gala in September of last year, it’s usually tokenized, there’s one Native included. It makes me so mad.

And so that’s why I wanted to write this story, was just to at least try my hand at honoring the self-representation that I do see among Native designers and just show a little bit of what that scene is, because I usually participate in the fashion show at Santa Fe during Indian Market in August. This year’s the 100th anniversary of SWAIA and I also do modeling mainly just for Native brands.

And the reason is, I just want to do what I can to promote Native brands with excellence and to make them and us more visible. So that was where the story came from. It was just like my itching desire to do something, even though it’s not like I’m at the center of the fashion industry or anything like that. And like, that’s not what I need to be, but I do want to contribute in whatever way I can.

And additionally, this idea of the toxic relationship and what it costs to grow out of that, because that’s such a common thing for Native women. I don’t know if I’ve unfortunately memorized the statistics about how much more likely they are, like Black women, to experience domestic violence and to just be dealing with intergenerational trauma issues around abuse. And so, yeah, that one.

I heard this concept of a hyperdrive, which is like a story where you write or you read it to enact a change. And so I wanted to write a story that could do that, that if a person kind of in an abusive relationship read it, that it might be so charged that it might push them to do something, like set a boundary, like this guy trying to break in.

And obviously, I mean, they love each other, but his behavior is endangering him and her. And if she stays with him, she’s enabling him. And so the only way that the characters can grow is through separating, and that separation causes extraordinary, almost terror. And this question of like, is healing from toxicity even worth it, or do you just let your children do that? Because it’s too much on these two people to try to change. And we hear so much these days about how you need… there’s this moral onus to become less toxic and become a better woman or stronger woman. But I was reading, You Don’t Know Us Negroes by Zora Neale Hurston.

And I was reading something in there about how she had, you know, there’s a, there’s a shadow side to like strong, strong feminism to where it can be so hard on you, on me, or as I want as the woman to where it’s so much harder on you to try to forge new pathways of independence and healing that women end up leading that.

I think of that song on the new Kendrick Lamar album, where the couples fighting with each other, “We Cry Together,” and it’s like…. I don’t know. I feel like this is a big issue in communities and color for toxic and dysfunctional relationships. And it ends up getting put on this, like castigating each other thing.

Whereas I’m interested in transformative justice where, how can you do something that helps both of you, even if it sucks in the time being. It’s intentional in that story that the friend urges her don’t call the police, they won’t call the police on him. He’s not going to die. Like it’s okay. And it’s, it just sucks for everybody, but they’re trying their best. And it’s like a moment of, I guess, real growth.

Deesha Philyaw: Absolutely. That story and so many of the others have just these really compelling women characters, and I’m not going to take us on a tangent, but I feel like you started alluding to this, I think, in your response just now, that the burden of healing, it falls disproportionately on the women of color in these communities and in these relationships.

And so among all of your really compelling characters, we talk about how we love Florence. Do you have a favorite character from the collection?

Chelsea T. Hicks: My favorite character is in “Brother.” She’s the character who has grown up on the reservation and is encountering the California Osages. And her name changed a few times, so I need to remind myself what it is, but I love her because she’s the one who’s furthest from my experience.

And so I just had a lot of compassion and research in writing her, because I didn’t grow up on our reservation. And I just feel like she’s so generous toward the reconnecting Wazhazhe at her dances. And I just love her complexity because she’s like having a crush on this California Osage guy at … ceremonial dances.

And she kind of knows that she’s not supposed to have a crush on him because he’s like the California Osages, the infamous California Osages, who, like, they don’t know shit. And like, I just, I love her vulnerability. Like she’s trying to keep them at arm’s length. But at the same time she wants to help them.

And I just feel like it speaks to the…. even though we have these different tribal politics and things that we’re working through, Osage people are really loving and kind, and like, they’ll do anything for you, as long as you feel like you have each other’s back and nobody’s threatening you or trying to disrespect you. And so I just like her incredible generosity.

Deesha Philyaw: So this is Mina that you’re talking about?

Chelsea T. Hicks: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah, that also means first daughter in Osage, it kind of gets used as a nickname.

Dawnie Walton: So our time together is in like hyperdrive. I cannot believe, but we did have one last question. And it’s just so wonderful and inspiring that you have this collection out. And so for the writers in our audience, leave us with a bit of inspiration. Tell us the story of your first ever short fiction publication, anything, remember the year, the story, the acceptance letter, any of it?

Chelsea T. Hicks: So, in the “Onomatopoeias For Wrangell-St. Elias,” noted in my bio that you all so graciously read. I had this one poem, it was a pantoum. It was written in response to sounds gathered from Wrangell-St. Elias National Park by a sound artist named Eric DeLuca. And we were collaborating as like an undergrad-grad pair.

And so I looked up whose land that was–and it was Ahtna and Athabascan land and I included words from those languages. And we made a script for different readers to read kind of like an animate perspective of the land. And it was published in UVA’s… like a student zine, you know, only, I think, 500 copies made and hand-distributed, and the launch party was at this cool coffee shop.

And it was just one of those moments of like, “Oh, wow, these are the cool kids.” And yeah, it was like, I remember it had kind of a cardboard, you know, it reminded me of brown paper package wrapped up in string kind of thing. It was “Okay, this is a zine. What’s a zine?” Yeah, it was just so exciting. And I kept it framed.

But yeah, I think that for the writers out there who are listening, that publishing anywhere that inspires you, however small, is a really great way to build up your stamina in writing.

Because at least for me, I know that any type of affirmation that’s community-minded that I do receive, kind of puts some fuel in my engine. So I would say, do submit to those blogs and zines, or even start a zine yourself, if you feel so inspired and just build up to those larger publications because it takes, so much time in this industry to get to that place of, where you can kind of shout it out loud and people will hear you. So don’t hesitate to kind of fuel your own engine with wherever you can find that community to share your work.

Dawnie Walton: I love that, Chelsea T. Hicks, thank you so much for this wonderful conversation for this beautiful collection. Definitely, I agree with Kali, it is unlike anything I’ve read before. So thank you for that.

Chelsea T. Hicks: Thank you, Dawnie, and thank you Deesha. This has been a true delight to talk about these things with you.

Dawnie Walton: And thanks to our audience for joining us today. If you enjoy today’s conversation and want more, become an Ursa member by subscribing at apple podcast, or by going to ursastory.com/join. You’ll help us produce our original stories and you’ll support our work on this podcast, as we turn you on to our favorite writers and short stories. You can support this podcast by leaving a review and a comment in Apple Podcasts. Talk to you next time.

Thanks for reading (and listening)!

Ursa is a new home for short fiction, from some of today’s most thrilling writers, supported by you.

Get email updates:

Subscribe to our podcast:

Support our work: Become an Ursa Member

We’re on a mission to build a new home for audio short fiction, with an emphasis on spotlighting underrepresented voices. You can help fund Season Two of our podcast and get exclusive, ad-free bonus episodes. Join us today: