On Episode 10 of Ursa Short Fiction, Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton welcome writer Michael A. Gonzales for part two of our deep dive into the life and work of Diane Oliver, who published six short stories before her death at age 22. (Part one of our series is here.)

Diane Oliver was just a month away from graduating from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop before she was killed in a motorcycle accident in Iowa City, Iowa.

Gonzales first introduced Philyaw and Walton to the work of Oliver — he published an essay about the writer in The Bitter Southerner earlier this year.

On this episode, Gonzales talks about his work digging into the archives to put a spotlight on Black authors who never got the recognition they deserved, or whose books are now out of print. His column for Catapult, The Blacklist, has shared stories about authors including Charlotte Carter, Julian Mayfield, Henry Dumas, and Darius James.

Subscribe to the podcast in Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, or wherever you like to listen.

About the Author

Harlem native Michael A. Gonzales is a cultural critic/short story scribe who has written for The Hopkins Review, The Paris Review, Longreads, Wax Poetics and Soulhead.com. Gonzales writes true crime articles for Crimereads.com and wrote the series The Blacklist about out-of-print Black authors for Catapult. His fiction has appeared in Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression edited by S.A. Cosby, Killens Review of Arts & Letters, Dead-End Jobs: A Hit Man Anthology edited by Andrew J. Rausch, Black Pulp edited by Gary Phillips and The Root. His latest short story “Really Gone” was published in the Summer 2022 issue of the Oxford American.

Episode Links and Reading List:

- “The Short Stories and Too-Short Life of Diane Oliver” (Michael A. Gonzales, The Bitter Southerner, 2022)

- Ursa Short Fiction, Episode Nine: The Life and Stories of Diane Oliver, Part One

- “Mint Juleps Not Served Here” (Diane Oliver, Negro Digest, March 1967)

- The Blacklist essay series on out-of-print books from Black authors (Michael A. Gonzales, Catapult)

- Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 (2019)

- “Beautiful Women, Ugly Scenes: On Novelist Nettie Jones and the Madness of ‘Fish Tales’” (Michael A. Gonzales, Longreads, 2019)

More from Deesha Philyaw and Dawnie Walton:

- The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, by Deesha Philyaw

- The Final Revival of Opal & Nev, by Dawnie Walton

Support Future Episodes of Ursa Short Fiction

Become a Member at ursastory.com/join.

Transcript

Michael A. Gonzales: There was not a lot being done on Black literary figures, and that’s why I kind of took the responsibility to do that.

Dawnie Walton: Hey y’all, I’m Dawnie Walton.

Deesha Philyaw: And this is Deesha Philyaw.

Dawnie Walton: And welcome to the Ursa podcast, where we geek out on all things short fiction. On this podcast, we’ll interview authors, discuss collections and stories we love and shine a light on new writers and those who never got their due.

And at Ursa, we’re not just talk, we’re publishers, too. Over at ursastory.com we’ve created a new home for short fiction from some of today’s most thrilling writers, as well as emerging voices, with stories you can read on your phone and audio stories that you can listen to right here in your favorite podcast app. We’re doing all of this with support from you. Become an Ursa member today by subscribing in Apple Podcasts, or by going to ursastory.com/join.

Deesha Philyaw: If you’ve checked out Ursa before, you may have heard our episode about a hidden figure of the literary world, Diane Oliver, a young Black woman who published several pieces of fiction by the time of her death at age 22. Today, we’re thrilled to go even deeper about her talent with our guest, the writer and cultural critic who first brought her to our attention, Michael A. Gonzales.

Dawnie Walton: Welcome, Michael.

Michael A. Gonzales: Good afternoon, it’s great to be here, thank you.

Dawnie Walton: And to tell the people a little bit about you. So, you’re a Harlem native and a cultural critic, short story, scribe and essayist, who’s written for Vibe, The Source, The Paris Review, The Village Voice, Wax Poetics, The Wire UK, Longreads, and Pitchfork. Your short fiction has appeared in, Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression edited by S.A. Cosby—wonderful writer—Taint Taint Taint, and also Black Pulp, edited by Gary Phillips.

Deesha Philyaw: Welcome, welcome, thanks for chatting with us today.

Michael A. Gonzales: I’m so happy that we’re talking about Diane Oliver, I mean, as you know, I mean, she’s somebody I just discovered a few months ago and I’ve been researching her and writing about her, and it’s been a thrill.

Deesha Philyaw: And as I mentioned in the intro, you are the reason we even know who she is because you reached out to me and said, “Hey, I’m doing this article on Diane Oliver, I want to get some thoughts from you about her work.” And I was really embarrassed to say I had not heard of her, and so, we all are really thankful that you are reintroducing her to the reading public.

Michael A. Gonzales: Well, I have to tell you, you’re not the only one. I mean, I didn’t even know about her until November. One of my friends was moving in and in the process, he sent me this anthology called Right On!, that was a book from 1971 of short Black fiction, and for some reason, I always say that the gods directed me to this story. I just opened up the book and I honed in on her story and I read “Neighbors”, and after reading “Neighbors”, I was like, “Oh my goodness,” like I needed to know more about this woman. I couldn’t understand why so many literate and literary people I knew had never heard of Diane Oliver.

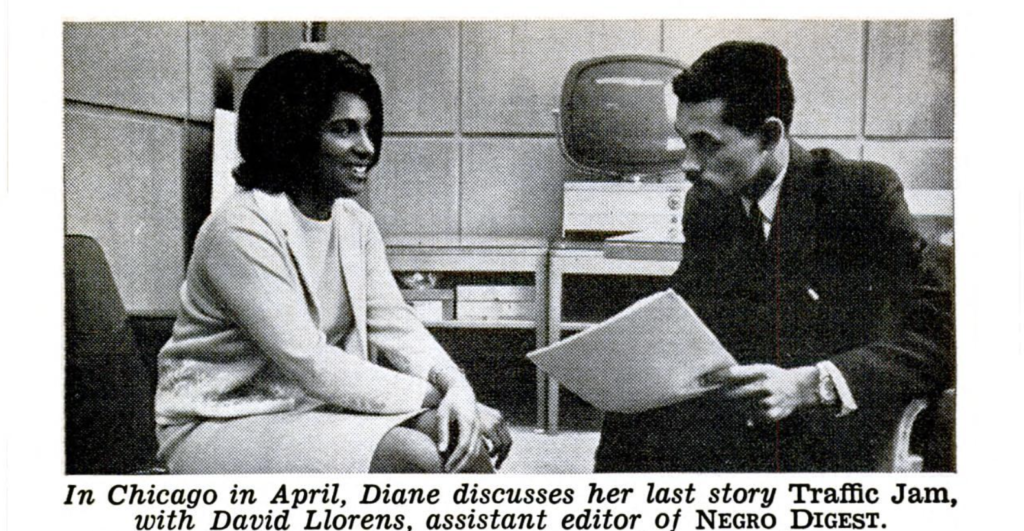

So, I was intrigued not just by her work, but by her legacy. And so, I just started digging, I mean, thank God there’s issues of Black World, which was actually called Negro Digest first and then it became Black World, that’s where I found a few of her short stories. And I also found out some autobiographical facts about her that helped me along in putting together this essay on her that’s actually on The Bitter Southerner now.

Dawnie Walton: Amazing. Her name was also a name that was completely new to me, and we discussed those stories from Negro Digest in-depth and “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam”, we both just really, really love those stories, and we’re sort of astonished by the talent that she had in the promise. But we were kind of doing some rudimentary research about her writing, there was really scant information available about her. We found, I think, four stories of her online and we learned a little bit of biographical information about her North Carolina roots, and we also knew she was just mere days away, really, from earning her MFA at an Iowa Writers’ Workshop when she was killed in a motorcycle accident. So, I just wonder if you can take us through a little bit of your research process in sort of like really digging into it and what new details you were able to discover.

Michael A. Gonzales: Well, whenever I get attached to a subject, I become obsessed, and I don’t really go to the library as much as I used to, but I was able to find a lot of things online. I mean, when I start researching, I go to Google, but I also look at every search engine that I could possibly think of. I look at Yahoo, I look at Bing, I go to Google Images and see if I could find anything, I go to Google Books, which is where I found a lot of stuff.

There were things that had been done for some academic journals on her background and I found some information about her old writing teacher who was one of her mentors, a guy named Pete Taylor, who I had never heard of either, but apparently, he was a major short story writer in the ‘40s and ‘50s, and The New York Times, they had called him one of the best short story writers. I mean, there’s just so much information, you just have to know where to look for it. And so, I just had a lot of patience and just started digging.

Dawnie Walton: Yeah, one of the first things you mentioned is the anthology you found “Right On!,” and I was like, “Wait, this is not the teen magazine…

Michael A. Gonzales: No.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s exactly what I thought, too.

Dawnie Walton: Right On!

Deesha Philyaw: I was so confused.

Michael A. Gonzales: It came actually around the same time and I don’t know who—because I’m a Right On! baby, okay? I grew up Right On! magazine.

Dawnie Walton: Of course.

Deesha Philyaw: Yes.

Michael A. Gonzales: And they even spelled it, I mean, they even had the

Dawnie Walton: Okay, with the exclamation mark.

Deesha Philyaw: The exclamation mark!

Michael A. Gonzales: I was like, “Who does this?”

Dawnie Walton: I was like, “Let me find out she was writing for Right On! magazine.”

Michael A. Gonzales: Oh my God, no. But you know, in the ‘70s, there were a lot of Black anthologies in the ‘60s and the ‘70s, a lot of Black anthologies that had Black short stories, Black plays, Black poetry. I mean, nowadays I’ll see singular collections, but I won’t see a wide collection, you know what I mean? That has a lot of different writers that’s part of a collective or part of a generation or whatever. And so, Right On! was—I’ve never even seen this book in used bookstores and believe me, I used to live in used bookstores.

Dawnie Walton: Well, that sort of segues into the next question that I have for you. So, I very much appreciate not only a man who reads, but a man who reads stories by and about women, and you’re a writer and as writers we are often finding inspiration in each other. So, just wanted to ask you, what in these stories by her spoke most deeply to you, Michael as a writer or as a reader?

Michael A. Gonzales: I like reading about the South during Jim Crow or coming out of Jim Crow, but she wrote about it with such sensitivity, and she just had a style about her that just kind of pulled you into the stories. I hope this doesn’t come across as an insult or anything, but it wasn’t over intellectualized or anything that was above your head. To me, it was just like, she wrote this in—there was a style to it, but it was also a simplistic kind of way of bringing you into these topics.

I loved it because it kind of reminded me of reading Shirley Jackson, who could make the everyday kind of horrifying. And we all know racism whether it was during Jim Crow or yesterday, is scary. Especially when you’re put in certain situations, you know, when you read the story in “Neighbors”, and you realize this family is having to deal with whether or not to send their six-year-old son to integrated school to following day and the repercussions that could come from that, whether it’s somebody spits on him or somebody shoots him.

I mean, this is what they were having to deal with, and here, she opens the story with that tension of the protagonist who’s the boy’s older sister, and you just kind of follow it through. And I’ve read a lot of stories from that era, and she just pulled me into it, you know?

I mean, she’s writing about the South from the perspective of somebody who’s finished school and going to college, but she also knows these people. I mean, these were the people that were a part of her community as well. I mean, I think a lot of times people don’t realize that Jim Crow and segregation—it’s like, you could be living down the block from a Black millionaire, but he couldn’t go anywhere because of these rules or whatever. So, she saw a lot that was going on. I mean, her parents were educators, so she saw a lot in terms of what was going on with the integration at that period.

Dawnie Walton: And in terms of her, you know, would love if you could shed any more light on her background, her family life. She was pretty middle class, right?

Michael A. Gonzales: Yeah. I mean, when you look at pictures of her, she has this almost debutante kind of look, she looks very middle class, like the kind of young Black women, there were features on the society pages of Jet and Ebony. And it was kind of funny because a year before I was writing about people who came out of like the Jack and Jills or people who came out of more educated Black society.

And she was one of those kinds of people, but at the same time, I think a lot of times, or we perceive people of that—what do we call it? That station or whatever, to look down on people who have less than them, and maybe some of them do, but she wasn’t that kind of person, you get an understanding from her. I mean, there’s like, you know, she may not have lived through all the things that she wrote about, but she wasn’t telling any lies. I mean, she knew what she was talking about.

Deesha Philyaw: When you said, “That class of folks,” I immediately thought about Lawrence Otis Graham’s, Our Kind of People.

Michael A. Gonzales: Yes.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, Diane Oliver has that background on paper, no pun intended but then her stories as you said, not only do they focus on working class folks, but she does it in a way that’s not othering, and it’s not diminishing, it’s very respectable.

Michael A. Gonzales: is not judgmental at all, you know? I mean, that’s the thing, I mean, with the exception of… what was the story? “The Closet on the Top [Floor],” where she writes. I found that in anthology, so I’m not sure if you read that, but that was about the young Black woman who goes to college, she’s the only Black person there and what she’s dealing with her classmates and roommates and that kind of stuff, to the point where it literally drives her crazy.

Dawnie Walton: Wow.

Michael A. Gonzales: I mean, it is deep. I mean, I’m laughing but it’s more like, you know, this is what racism can do. You know? I mean, people don’t understand the anxiety or the stress that comes with people who look at you like you’re a creature or who looks at you like you’re so different or whatever. And the girls in the college, they didn’t say anything to her face, but they whispered a lot, and they looked a lot, and to the point where—I mean, she literally went into the closet and didn’t want to come out.

Dawnie Walton: I’m glad you brought that story up, because that was actually one of the ones that we could not find “The Closet on The Top Floor”, and the other was “Mint Juleps Not Served Here”. Can you tell us a little bit about that story because I’m very curious.

Michael A. Gonzales: “Mint Juleps” was—Oh my God, it was like this wild kind of gothic story about these Black people who basically just go live in the woods, and they didn’t want to have to live under white authority. And it’s a very brutal kind of story. I don’t want to give away too much of it, but literally that one was more of the Southern gothic kind of thing, like the kind of stories that—like Flannery O’Connor or Faulkner, or… you know, even early Truman Capote might have, you know?

I’ve always loved those kinds of stories of people who really don’t want to be bothered with civilized world, people who kind of cut themselves off from, whether it’s the government or whatever, they just want to live their lives and be left alone. And basically, “Mint Juleps” is about a couple with their mute son who wants to be left alone, and they’re not left alone.

[Music]

Dawnie Walton: And you also mentioned, you sort of saw an influence, like a horror kind of influence in some of these stories and reminded you in some ways of the work of Jordan Peele. And I’m just sort of wondering, what other kinds of influences or what artists do you kind of see Diane Oliver in their work?

Michael A. Gonzales: To tell you the truth, I’m a big fan of Shirley Jackson, I love “The Lottery”, I love her short stories, and I don’t know if Diane Oliver had ever read or even knew who Shirley Jackson was. I mean, she was a bright young woman; she was living in New York in the early ‘60s when Shirley Jackson was publishing in The New Yorker. So, I don’t know if that was ever at influence, but to me it was almost like she kind of brought to mind Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor, and I like horror stories that aren’t necessarily about people getting killed off or a lot of blood or whatever, I like…

Dawnie Walton: Psychological horror.

Michael A. Gonzales: Psychological horror, exactly, or even like the kind of horror like the Asian directors were doing at one time, like you always feel like there’s some creepiness going on. You don’t know exactly what it is, but it just feels scary. And to me, I wasn’t really trying to say that she was a horror writer, but I was just equating racism with horror. And to me, a prime example of that is looking at one of my favorite movies and one of the scariest movies is the original Night of The Living Dead, right? And you’re like, after this guy has battled zombies all night long, he gets killed by a white gang. And it’s like, for real? This Black guy fought zombies all night, but the thing that killed him was the white mob.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Michael A. Gonzales: And that’s kind of, you know, when I was reading Diane’s stories, like even reading “Neighbors”, I mean, it was like, “What’s going to happen?”

Dawnie Walton: Yeah. I was going to say the tension of them in that house sort of waiting…

Michael A. Gonzales: Exactly.

Dawnie Walton: …for something to happen, waiting through the night, trying to make this decision. There’s lots of tension in that.

Michael A. Gonzales: I mean, okay, I guess this is a spoiler, but I didn’t…Like, the way they decided at the end not to send the boy to school, I was shocked because every civil rights story you read or you see on a PBS special is about how the family said, “Okay, forget all of that, we’re going to send this kid to school anyway.” And this family was like, “You know what, we don’t need this.”

Deesha Philyaw: See, I read it as an ambiguous ending, I thought it was a little gray.

Dawnie Walton: I think I originally read it as they didn’t send him, but it was a little uncertain.

Michael A. Gonzales: But whether they sent them or not, it was still, like you said, the tension that was going on. I mean, even the tension of when she’s on the bus, she’s already thinking about this. I mean, this is like obsessed her whole life. She’s walking through the neighborhood and everybody from the neighborhood bum to the neighborhood gossip, is talking about this little boy going to integrated school. I mean, there’s a lot of pressure on them and then there’s a lot of like what’s going to happen? Are they going to kill this kid? Are they going to blow up the house? It’s just, you don’t know.

Dawnie Walton: “The Closet on the Top Floor”, the way you describe it—so, a character who is being watched and examined by a sort of white gaze, kind of actually had me thinking a little bit about another part of your essay. So, you also spoke with one of Diane Oliver’s—I think, was she acquaintance from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop?

Michael A. Gonzales: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: Suzanne McConnell? Yes. So, I went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I will say it’s a very different place. I actually found some wonderful community, there were several Black women in my class, and we were able to sort of build a family and find our readers among each other. And I know that that was not the case for her in the 1960s.

Michael A. Gonzales: I mean, I think when she went, it might have been like—it was relatively new. I don’t even know if it had the same kind of cache that it has today. I mean, the fact that she and John Edgar Wideman were there at the same time, I kind of guess indicates what kind of program it was. Like these were some serious writers coming out of there. But when she went, I don’t know if she realized how much ground she was breaking.

Dawnie Walton: And I kind of wonder if she felt supported or actually that she was known. I mean, I think…So you quote Suzanne McConnell is saying that Diane seemed cautious and careful, but I suppose considering what she was surrounded by, she had to be that way.

But I found it really telling that when Suzanne McConnell sort of wrote about Diane Oliver’s death around the time, she actually got a lot wrong. She got the last name wrong, her place of origin wrong, and I’m not really sure what question I’m trying to ask, but just how did that strike you in terms of learning about Diane’s life and her experience that she might have found herself in, at such a tender age?

Michael A. Gonzales: I think we have to realize that a lot of this happened years ago. I mean, this was in 1966 when they were there. And I think when Suzanne wrote about it later on, it was 30 years later.

Dawnie Walton: Oh, I see.

Michael A. Gonzales: She wrote about it for…I mean, she actually went back and made some corrections to the essay, but no, I don’t think any of it was really intentional. I mean, I don’t know if I’m answering your question.

Deesha Philyaw: Well, I’ll share how I reacted to that because we are kind of looking to her –and this was us reading your essay, Michael—as someone who was there, and I think it speaks volumes about something that happens to so many of us as Black folks, specifically Black writers in white spaces, there’s our experience and our perception of it. And then there’s white people’s perception of our experiences, right?

Michael A. Gonzales: Exactly.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, Suzanne is saying she felt like she had to be careful and cautious, she was very thoughtful and not wild at all. And I said, “Wait, hold up, did she expect Diane to be wild, why?” And so…

Michael A. Gonzales: Well, you know what? I have to confess, that came out because we were discussing another writer that I had written about, this woman named…And the other writer I had written about had this whole wild background of booze and drugs and everything, and so Suzanne was telling me that Diane was the opposite of that.

Deesha Philyaw: Got you, okay. But I think the larger issue, you know, because in general, I think I’m always skeptical, right? And Suzanne says that she got along well with the fellow students, and it just made me kind of wish that we could hear more from Diane herself. And then, we think about the story of “The Closet on the Top Floor”, how much of that reflected how Diane actually felt in white academic spaces.

Michael A. Gonzales: You’re right.

Deesha Philyaw: And so, I was just thinking about what I’m calling Diane’s triple consciousness as a Black woman building on Du Bois’s concept of how Black folks have the double consciousness but as a Black woman, this triple consciousness. And so, those of us who are writing today, like the three of us, we can shout from the rooftops, we’ve got social media. The future generations won’t have to wonder so much about the three of us. But I’m thinking now more broadly and would love your thoughts on this, Michael, about Black literary legacies and how they’re shaped, you know, who gets to tell the storyteller’s stories?

Michael A. Gonzales: I mean, that’s a great question because I mean, that was one of the reasons I started writing these literary essays in the first place. I first started writing it for Catapult, I was writing a column over there called The Blacklist. And basically, I came up with The Blacklist because I wanted to write about writers that basically kind of were out of print, a lot of people hadn’t heard of them. So, the first one that I did was Negrophobia by Darius James, and then I later on wrote about Henry Dumas, Kristin Hunter who wrote The Landlord and Julian Mayfield.

I’m fascinated with Black writer’s lives anyway, you know what I mean? But then when you read about these writers who…I mean, it was a different time, a different era, and just so many writers who were big names at one time, they kind of fade away sometimes. And I don’t know why that is. I mean, I think my whole thing was I saw like, there was a new reissue of some Beat Generation novel, and I’m like, “How many damn Beat Generation novels do we need?” Like how many reissues of William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac can one person stand?

Meanwhile Julian Mayfield is out of print, Charlotte Carter is out of print, Henry Dumas is out of print. You know, these books are going for hundreds of dollars on Amazon and nobody, Black, white, or whatever, hardly knows who these people are. Henry Dumas is probably the most famous because he was a discovery of Toni Morrison’s, after his death, and she published a few of his stories. But there was not a lot being done on Black literary figures.

And that’s why I kind of took the responsibility to do that. I mean, I wrote an essay on Ronald L. Fair, who wrote the novel that Cornbread, Earl and Me is based on, I wrote an essay about him for a book. And that kind of started me on this whole thing. I mean, he was a Chicago writer, not a contemporary of Richard Wright’s, but like a generation afterwards and he wrote three novels and basically, just kind of faded away.

I mean, and so when I wrote about Cornbread, Earl and Me, was because it was based on this Blaxploitation movie that I grew up with, you know, Larry Fishburne’s first movie, and that was one of my first essays on Black literary writers. And then for Catapult, and I’m telling you, it’s fulfilling to me because I want people to know about these writers.

I always feel like there’s a shame that these writers aren’t better known, and nothing against, you know, I love all the big names. I love Toni Morrison, I love James Baldwin, but a lot of times people act like those are the only two, and there’s so much more, there’s so much more now, there’s so much more 30 years ago.

[Music]

Dawnie Walton: One thing that Deesha and I discussed when we went very deep with the stories, we sort of noticed the four stories that we read were about women and sometimes the choices that women make. So, we read “Neighbors”, “Key to the City”, “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam.” And they all kind of end on a note of resignation looking at a choice that the women characters are kind of either circumstance has forced them to make it.

And so, we kind of thought, “Wow, if Diane Oliver had lived longer, how might that have changed? Might she have written work where the characters are a little bit more rebellious or a little bit more kind of not resigned in that same way.” And so, I was just curious how you think that Diane Oliver might have evolved as a writer, how her sensibilities might have changed had she lived longer?

Michael A. Gonzales: I don’t know. I mean, I would love to have read a novel from her, I would’ve loved to see and what direction she would’ve gone in. I mean, Diane Oliver, she had been writing for a few years before her death in 1966, but I think like some of those last stories, she was becoming a better writer or more haunting writer, a lot of times the story just felt richer.

And during that era, I don’t, you know, I grew up in the 70s, so I remember my mom having books from Ntozake Shange and Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison and, you know, writers like that, but we didn’t have a lot of the ‘60s stuff, except for in anthologies. So, I don’t know where Diane Oliver would’ve gone because she kind of was in the middle of, you know, like between generations, it would be curious to find out where she would’ve gone. I mean, I don’t know if there were any archives. I’m sure there must have been notes.

Dawnie Walton: Well, I do know she does have, I think, a thesis on file at the University of Iowa that I’ve been trying to figure out how to get my hands on, yes.

Michael A. Gonzales: Oh really?

Dawnie Walton: Yes.

Dawnie Walton: I kind of started the process, and I’m trying to figure out how to do it.

Michael A. Gonzales: But that’s wonderful.

Dawnie Walton: And I’m not even sure, it might be versions of work that was already published posthumously because I do know that Negro Digest did a couple of posthumous stories by her, but it’s fascinating to know that there could be work of hers there that unfortunately never saw the light of day.

[Music]

Michael A. Gonzales: You know, one of the things that we were touching on was just talking about being a Black person in a white writer’s group, and I’m sure all of us had dealt with that at one time. I mean, when I started writing, I was writing more fantasy stories as opposed to more realistic stories, so I didn’t have a lot of kickback.

But I’ve heard so many horror stories from brilliant writers, Black writers, Puerto Rican writers, Dominican writers, of the things that they had to endure when they were part of all-white writers circles or all-white writers groups or whatever, whether it was a lack of understanding or people just zoned out on their stories because they didn’t feel they were important or something.

And I don’t get any of that from Diane’s writings, but I’m sure she must have…I mean, I wonder how she overcame being the only one, not just the only, you know, I mean, the only Black woman in this group. I mean, we’re dealing with a time that where sexism and misogyny on campus was rampant.

I mean, people think academics is a goody-goody, but you know, we know differently, and being in the mid-‘60s, when all of this stuff was going—I mean, even her white writing professor from undergrad, Peter Taylor, he encouraged her writing, but he didn’t want her to get too mixed up in writing about civil rights or writing about race. It’s the same kind of thing where they want you to do well, but then they want you to do what they want you to do.

Deesha Philyaw: Their way. And I read that in your essay where you mentioned that that was sort of his guidance for her, and I love that clearly, she ignored him. And she absolutely wrote about—not only did she write about the Civil Rights Movement, but she wasn’t on like that respectability tip, she was writing about working class people, she was writing about women in marriages that weren’t great, and that she was writing about women. And because so much of the narrative around the Civil Rights Movement that we’ve been given in fiction and nonfiction, does focus on men. And the women are always relegated to the background, but she centers the women in her fiction. So, she not only ignored her professor’s guidance, but she took it even further around class and gender. And so, I’m getting real badass vibes from her.

Dawnie Walton: That is true, yes. And I do, you know, as someone who has been through sort of the institutional workshop experience, it’s just as important to know what to ignore as it is, what advice to listen to.

Michael A. Gonzales: Oh, exactly.

Dawnie Walton: And your ear becomes very attuned to that kind of thing. So, the fact that she was able to do that, thank God for it.

Michael A. Gonzales: Yeah. I mean, I had a good friend of mine, I’m not going to say his name, but he wrote an excellent novel, and he told me when he was in the writer’s workshop that people were just saying negative stuff to him, or like spouting off or saying stuff is too racial. I don’t know why it’s always too racial when it’s about us.

Deesha Philyaw: That’s code for “this is making me uncomfortable.”

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Michael A. Gonzales: But, I mean, you don’t even have to write about stuff to make them uncomfortable to be uncomfortable, you know what I mean? Like you can write about driving around in your hooptie through the hood, smoking a blunt, listening to Earth, Wind and Fire, and they’re like, “I don’t understand,” like, why don’t you understand? Like, what the hell?

Deesha Philyaw: Oh, it’s okay if they don’t understand. It’s that they’re not centered when they’re—there’s something to be said for reading work where you and people like yourself aren’t centered, like, there’s the benefits of that and the pleasure of that. And I think it’s hard for people who are used to being centered in literature to then not be.

Michael A. Gonzales: Well, I mean, I think as Black writers, I mean, I know even with me growing up, I was blessed that I had somebody at home who actually read Black work. I mean, because a lot of writers, they don’t read Black fiction or other Black writers into until they’re in college or something.

I mean, I was reading Ntozake Shange when I was a kid, I mean, I was reading For Colored Girls and books of poetry and the stuff that my mother had on her shelf because she never censored me from reading anything but at the same time, it’s like, there are so many writers that I know who didn’t discover those voices until years later.

So, a lot of times, they don’t know how to write about themselves. And I always tell people that, two of my biggest influences growing—well, one of my biggest influences growing up was Richard Pryor because of the way he wrote about the hood. A lot of writers, they don’t have those kinds of influences in—they may even try to write “white,” and that doesn’t work too much either.

Deesha Philyaw: I can think of a writer who told me something similar that they thought as a Black writer, that to write seriously, you know, to be taken seriously, to be considered a literary writer, that they had to center white folks, and then thankfully, this is a writer who eventually was like, “Nah, I’m not doing that.” But I think some people do get stuck there.

Or even just think about Toni Morrison, that New York Times critic that wrote about—I believe it was The Bluest Eye and was so condescending and referred to it as provincial and hoped that Morrison would eventually grow up and stop writing about Black people and Black life.

Dawnie Walton: It’s just unbelievable.

Deesha Philyaw: It’s wild.

Michael A. Gonzales: It’s crazy, I mean, a lot of those guys, especially one of my heroes is Chester Himes. Chester Himes is coo-coo for Cocoa Puffs, and some of his early literary novels before he started writing the Harlem gangster novels, but people were basically dismissive of it, and part of him going to Europe—I mean, I don’t even know if he was ever really happy in Europe. He was just less mad, but part of that was like, him and James Baldwin both, they were like, “You know, if we stay in America too much longer we’re going to wind up hurting somebody or killing somebody.”

And I’m sure a lot of that probably came from dealing with editors who didn’t understand where they were coming from. Even when Richard Wright published his landmark books, Native Son and Black Boy, there’s chunks of it that’s taken out by the Book Club of America, which was a big sponsor, because they didn’t want to make people uncomfortable. I mean, it is like, “Wow,” when I read that was an actual thing, I mean, I was really hurt for Richard Wright, you know?

[Music]

Deesha Philyaw: I am just thankful for this conversation that we…

Dawnie Walton: Yes.

Deesha Philyaw: We got to speculate a little bit, we got to celebrate Diane Oliver a little bit, and I think about what Alice Walker did for Zora Neale Hurston, and what Dr. Harryette Mullen did for Fran Ross, and Michael, I really hope that your efforts—not just for Diane Oliver, but for all of these writers who are out of print, can have the same kind of effect and introduce these writers to, you know, I was going to say another generation, but hell, our generation…

Michael A. Gonzales: Right.

Dawnie Walton: Right.

Deesha Philyaw:…And generations to come and really give them their rightful place in our cannons and on our shelves.

Michael A. Gonzales: Well, I will say if anybody wants to read more of underappreciated or out of print Black writers, they can go to Catapult and read my column, The Blacklist, The Ronald L. Fair essay or incorporator under me, was actually published in a book called Sticking It to the Man: Counterculture and Popular Fiction, 1950-1980.

And I mean, those are really good places to start, I think. And I hope more Black writers…I know one of the writers that I wrote about actually got back into print Charlotte Carter, who wrote the jazz mystery novel, Rhode Island Red, her books, actually got picked up again because of my essay.

Dawnie Walton: Wow.

Michael A. Gonzales: And so, I was very happy about that. Some of the writers, they’re still alive, I mean, they’re not dead, they’re just being pushed out or pushed away or whatever with…Charlotte Carter got all her books reprinted and she’s coming out with a new novel next year, so…

Dawnie Walton: Amazing. Thank you so much for that work, I am going to bookmark that Catapult column and also try to find that anthology Right On!, right? I need to get my hands on that one.

Michael A. Gonzales: Oh, yeah, you would like that.

Deesha Philyaw: We can do a whole episode.

Dawnie Walton: Okay.

Deesha Philyaw: We need to have a Right On! episodes.

Dawnie Walton: Yes, I love it. Thank you so much, Michael A. Gonzales for joining us today.

Michael A. Gonzales: Thank you so much. I was so happy to be here, and I’m glad we got it together.

Dawnie Walton: Me too. And if you enjoy today’s conversation and want more, become an Ursa member today by subscribing on Apple Podcast, or by going to ursastory.com/join. You’ll help us produce our original stories and you’ll support our work on this podcast as we turn you on to our favorite writers and short stories. You can support this podcast by leaving a review and comment on Apple Podcast. Until next time.